The Trauma Code: Heroes on Call (Netflix)

Park Soomin: From his very first day on the job, Dr. Baek Kang-hyuk (Ju Ji Hoon), an extraordinary surgeon who “has the hand of God,” speeds around the emergency room and rushes out of the hospital to be on the scene of accidents. “To keep our patients’ hearts beating,” he says, “we must keep running.” No matter the crisis at hand, Kang-hyuk performs life-saving miracles with unparalleled surgical skill, plus almost surgical decision-making skills, navigating the absurdity of a system that puts profits ahead of human life with a touch of humor. Maybe such dramatic turns are only possible in heroic medical dramas, but The Trauma Code stays rooted in reality with its main position that “severe trauma can happen to anyone.” It can strike anywhere, anytime, including to those meant to treat it: Han Yu-rim (Yoon Kyung Ho), a high-ranking colorectal surgeon under pressure who at one point becomes Kang-hyuk’s punching bag, collapses at the sight of his own daughter’s sudden car accident. And the leads aren’t just saving lives to put their borderline superpowers to work—they’re real people driven by a sense of ethics and solidarity. It’s why, when Kang-hyuk convinces Yang Jae-won (Choo Young Woo), another colorectal surgeon, to join the trauma center as a fellow and forego his secure future, it stirs up in him his humanistic sense of calling toward what “someone has to do” and a sense that everyone is equally responsible to carry the weight of the world together. No one should lose their life because they can’t afford to be admitted as a patient, and no one who can be saved should be allowed to die. So, when Cheon Jang-mi (Ha Young)—a nurse who became a senior at the largely undesirable trauma unit with less than five years of experience—reassures Jae-won by reminding him that “we don’t do this for the acknowledgment,” it rings alarm bells about society. In a world where profits and visible accomplishment are prioritized, how do we safeguard the values we can’t see?

The Spirit of the Beehive

Bae Dongmi (CINE21 reporter): In rural Spain, somewhere on the Castilian plain, six-year-old Ana (Ana Torrent) is at the community center watching a screening of Frankenstein. The girl becomes fully engrossed in the world of the movie, but she can’t fully grasp the true nature of it. That night, she asks her older sister, “Why did the monster kill the girl and why did they kill him afterward?” The sister, similarly perplexed by the details of the film, begins to spin her own version, claiming the monster is a spirit. “They didn’t kill him, and he didn’t kill the girl,” she explains. “Everything in the movies is fake. It’s all a trick. Besides, I’ve seen him alive,” she continues, “in a place I know near the village. People can’t see him. He only comes out at night,” adding, “Spirits don’t have bodies. That’s why you can’t kill them,” and that “it’s a disguise to go outside.” Our interpretation of the world creates a narrative, which, in turn, influences our own lives.

Ana takes a different way back from school so she can stop by the house her sister talked about in hopes of running into the monster. And one day, she encounters a man in military uniform there. Is this really the monster her sister described? Or is he a deserter on the run? The audience, of course, knows him to be the latter, but young Ana believes she’s finally face to face with the former.

To truly appreciate 1973’s The Spirit of the Beehive, a masterpiece of Spanish cinema and a part of global cinematic history, one must look beyond the film itself. Set in Spain in 1940, just as three grim years of the Spanish Civil War come to an end and dictator Francisco Franco comes to power, the backdrop paints a country scarred by wartime massacre and 110,000 missing persons, including thousands rounded up and slaughtered in bullrings, with the country yet to have fully recovered. Franco was in power longer than Hitler or Mussolini—a 35-year reign of brutal suppression where no one was permitted to bare their souls about the horrors of the Civil War. When Ana’s parents sit in prolonged silence and fall into deep despair, this history is the reason why. Children experience the effects both directly and indirectly, throwing themselves into dangerous games and retreating deep into their peculiar world of shared imagination. When The Spirit of the Beehive received its worldwide release in 1973, Spain was at the tail end of the Franco regime. The film was lauded for its evocative portrayal of post-Civil War anguish. In Korea, the film reached only a small number of eyes through festivals and arthouse showings. Now, after 50 years, it is at last receiving a proper release here. Some films fade within a month, but others, like this one, endure across the ages.

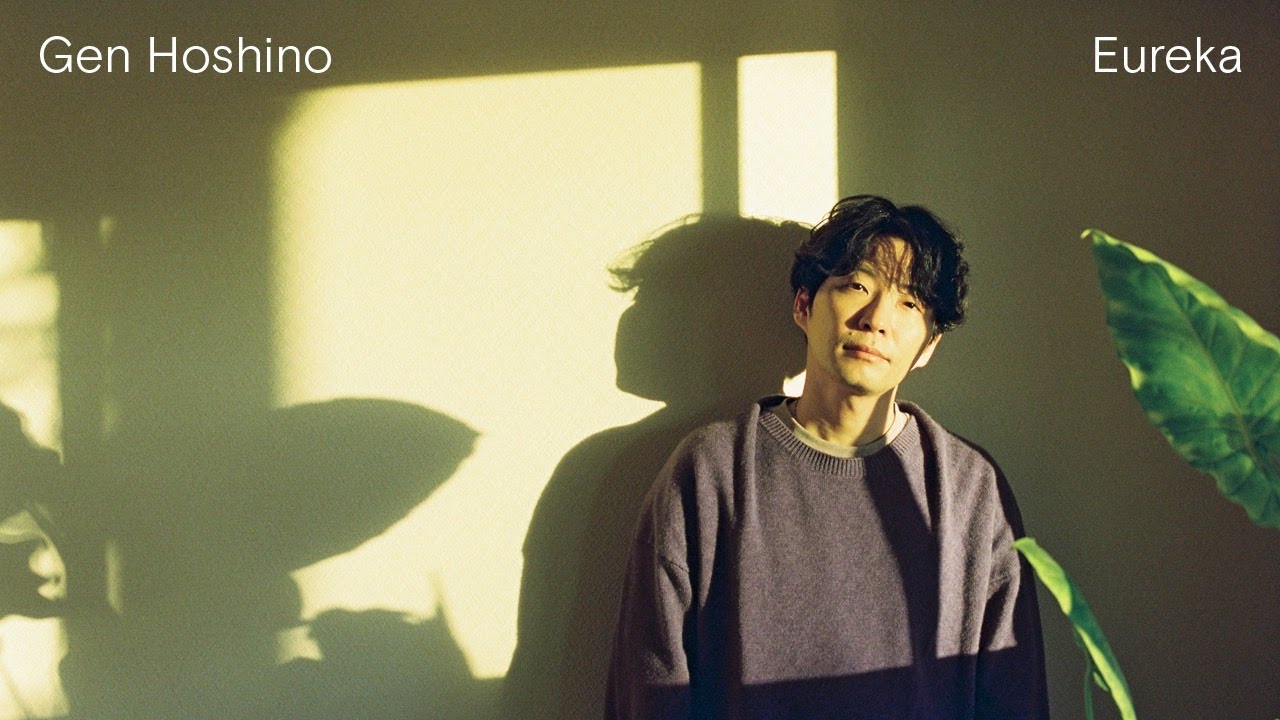

“Eureka” (Gen Hoshino)

Hwang Sunup (music critic): There’s nothing straightforward about placing a guess on how Gen Hoshino’s upcoming album—slated for this spring, and his first in seven years—will shape up. After his album POP VIRUS and the accompanying tour, he decided to take a step back from the pop star side of his public persona. The singles he’s released since have been wildly diverse and unpredictable. From the experimental, video-game-inspired soundscapes of “Create,” to the simple poppy “FUSHIGI” with retro beat and synths, the aggressive and progressive-adjacent “Cube,” the immersive and complex synth pop layers of “I Wanna Be Your Ghost” (feat. Ghosts), and the everlasting, unadulterated ’80s pop and new jack swing of “Why,” the tracks Gen Hoshino’s put out over the past several years have shown no clear consistency. He’s evidently taken the time to explore plenty of ways to break free from the labels placed on him.

The single “Eureka” stands out like a sort of pause for reflection in the midst of that journey. The simple piano backing directly reflects his ongoing pursuit of simplicity through subtraction. And the message behind the song—that life is a continuous cycle of loss and recovery, a quest to rediscover yourself—seems to echo his process of deconstruction and reconstruction in his music. Though his approach to and intentions behind his craft may have shifted, you can’t help but hear in the song the faint suggestion that what he seeks to attain is ultimately freedom—as if he’s out to reaffirm that, no matter how he frames his music, the essence of Gen Hoshino’s philosophy towards pop music never wavers or wanes. It’s like he’s running out after four whole years of hibernation, shouting “eureka!” and ready to share his new musical identity with the world. “Eureka” is brimming with warmth, offering an invaluable glimpse into the artist’s forthcoming album.

Brancusi Versus United States by Arnaud Nebbache

Kim Boksung (writer): The year is 1927. Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi, after breaking away from the stifling constraints of the traditional method he was trained in, has sculpted what would go on to become an infamous piece: Bird in Space. But what’s making it so notable isn’t that it’s being shown in the exhibition it was destined for in the United States—rather, that it’s *not* being shown. When Brancusi’s abstract sculpture is flagged by customs as an everyday object like a kitchen utensil and slapped with a heavy import tariff, it’s up to the courts–federal lawyers on one side, intellectuals on the other—to decide a question that puzzles us to this day: What is art?

The real, historic events of Arnaud Nebbache’s graphic novel Brancusi Versus United States take place a century ago in New York at a time when rapid industrialization is both thrilling and anxiety-inducing, while Brancusi, in Paris, seeks to capture the form and emotion of the era in Modern art. His “bird”—the last in a series of machine-crafted abstract shapes—defies classical conceptions of art at a time when perceptions of Modernism in America have yet to catch up. The sculptor, meanwhile, is kept abreast of the trial secondhand through letters while he and his peers in Paris wait nervously for a verdict.

Nebbache not only wrote a fantastic book, but also illustrated it in a style nearly as abstract as its subject matter. Some parts might strain those of us used to the clean lines of webtoons to interpret every intention on the page, but the challenge involved perfectly supports the point of the story.