Before it even had its world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, there were already reporters speculating that Broker had the potential to bag Song Kang-ho the award for Best Actor. Sitting on the jury this year were many high-profile actors, including French actor and jury president Vincent Lindon, all of whom easily recognized Song’s reputation, as this was the seventh film he had been involved with that was being considered at the festival. More importantly, the festival had to rely on star power to dispel the widespread belief that film festivals were in crisis due to the pandemic. And what name could be better than Parasite’s Song Kang-ho? Although Song had never received the Best Actor award at Cannes, every project he’s been involved with that has screened there has won an award, and he was invited as a judge last year owing to his long history there. He was a necessary choice, following the recent trend for Cannes to shed its image as catering only to challenging, niche art-house films and instead drive interest by recruiting big-name jury members to interact with the public.

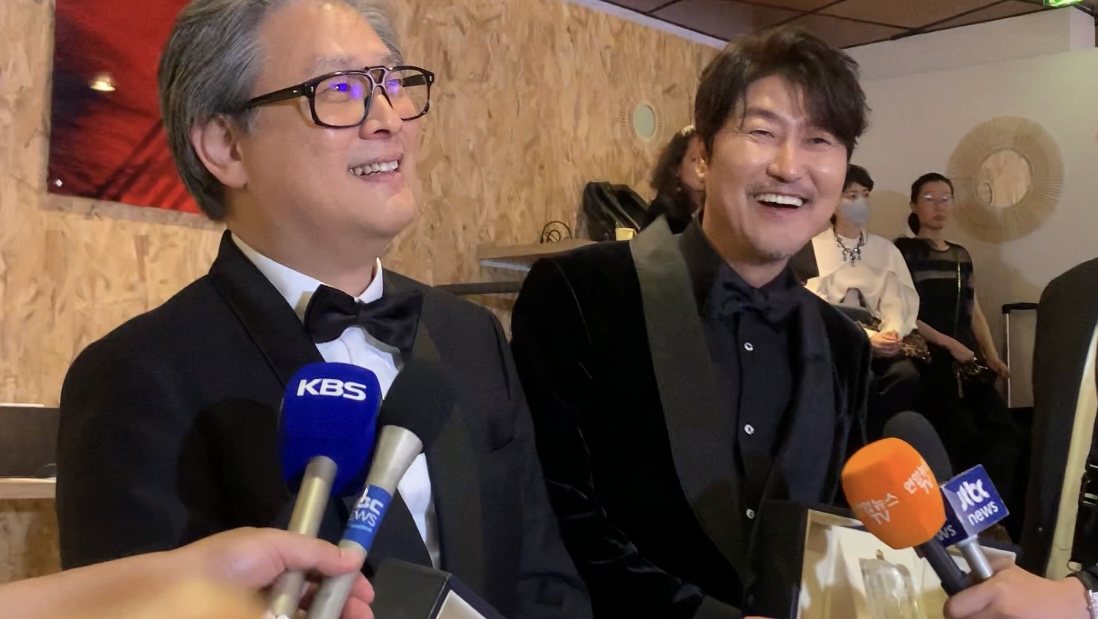

That’s why, when news broke to Korean media that the Broker cast and crew would be attending the closing ceremony—where invited films are virtually guaranteed at least one win—there was a strong belief that the award Broker was looking at would be Best Actor and would go to Song. This was the case even though they could tell after watching the premiere of the film that five actors—Song Kang-ho, Gang Dong Won, Doona Bae, Lee Jieun and Lee Joo Young—were equally represented throughout, with no one actor stealing the spotlight. Considering the prevailing opinion that the film does not live up to director Hirokazu Kore-eda’s previous works, as well as Song’s notable position in the Korean film industry as well as at Cannes, speculation about Broker’s pending win leaned more toward Best Actor than any other category.

After the list of films in competition was released, leading US media outlet Variety also suggested Song was second in line in terms of likelihood for winning the Best Actor award. (Korean media was full of articles predicting Lee Jieun would win Best Actress, but it was a different story elsewhere in the world: Zar Amir Ebrahimi starred in Holy Spider, a film based on the true story of a misogynistic murderer in Iran and screened early on at the festival, and was herself a victim of sex crimes and privacy invasion. Her early recognition made Best Actress the easiest award of the season to predict.) Per the rules of the film festival, where the voting process is kept secret, we’ll never know for sure what exactly tipped the Best Actor award in Song’s favor, but Cannes’ heavy reliance on Song made him a front runner from the start.

It wasn’t just Song—Korean films in general led the pack at Cannes this year. And it wasn’t just because posters for two of CJ ENM’s movies, Decision to Leave and Broker, were the most prominent outdoor advertisements seen around the Croisette, the busy main street of the film festival, either. As I sat in a Wi-Fi cafe working on a deadline, some foreign reporters who were waiting for their turns at an interview saw that I’m Korean and started conversations with me to ask me about Park Chan-wook and Song Kang-ho, expressing interest in their work on the very grounds that they were Korean films. Most notably, the previously sluggish race of films in competition gained momentum once Decision to Leave was announced and deemed a strong contender for the Palme d’Or prize; even before Cannes, the film had already generated such a flood of requests for interviews with the director that they had to be scheduled down to the minute. The movie received a 3.2 from the well-regarded English-language outlet Screen, making it the highest-ranked film among those in competition, and was given an average review by the French daily Le film francais, which has been critical of Park’s works in the past.

In short, it was easy to see Decision to Leave was the most popular film at Cannes from opening to closing ceremony during my time there. Acclaim for the film was so palpable that it almost felt like a letdown when Park won the award for Best Director exactly in line with expectations. Although not in competition, there was no denying the buzz surrounding Hunt, either. Hunt, which was given a midnight screening at the festival, is the directorial debut of Lee Jung Jae, whom I had a chance to meet along with his inseparable friend Jung Woo Sung at a press dinner. Children who recognized Lee for his role in Squid Game were constantly coming up to him for pictures, prompting a rare sight as Jung took to the other side of the camera for once.

What’s interesting is that the popularity of Korean film isn’t confined to the art film industry. In fact, it’s quite rare for movies from anywhere in the world to receive recognition for their artistic merit at the world’s three major film festivals and still have mass appeal the way Korean films do. Anyone who was ever drawn in by the promise of a Palme d’Or-winning foreign art-house film only to settle into a deep sleep in front of the screen will instantly sympathize with this sentiment. Contrast this with movies directed by Bong Joon Ho, Park Chan-wook, Ryoo Seung-Wan and Na Hong-jin—essentially, the greats of the genre film: Director Hwang Dong-hyuk, too, captured imaginations with his genre-heavy series, Squid Game. All these directors offer biting criticism of Korean society with their own distinct aesthetic and do so while lowering the barrier to entry for mass audiences through their top-tier genre entertainment.

A wider audience became aware of this quality of Korean cinema that sets it apart with Parasite, which won both the Palme d’Or and the Academy Award for Best Picture. Director Gina Kim, who currently teaches with tenure at the University of California, Los Angeles film department, says, “When I was teaching Korean film in Harvard in 2005 and 2006, so-called well-read students were interested in Korean movies, but after Parasite, the prevailing idea from the student body is that Korea is a culturally advanced country and a First World country in the world of film.” With its remarkable capacity to hone both popularity and artistic value, Korean cinema has expanded its reach to cinephiles and consumers of broader media alike. Even despite the linguistic and cultural barriers, foreign media often respond more favorably to Korean films than their domestic counterpart. With Broker, for example, I could feel that the foreign reporters I met at Cannes looked at the film even more favorably than the press in Korea.

It was a daring conclusion I came to earlier that the Cannes Film Festival needed Song Kang-ho. In reality, this applies not only to Cannes but to the many festivals and awards ceremonies around the world, and to Park Chan-wook, Bong Joon Ho and Korean film as a whole. It’s looking like Park’s Decision to Leave might have a particularly good chance of entering the Oscars race, including for Best International Feature Film. Netflix has also ramped up publicity around Squid Game in anticipation of the Emmy Awards season. Korean cinema goes one step further and can even play a socially significant role: giving the non-white population its place on the world stage, where it has traditionally been sorely underrepresented. A year after the Academy Awards bestowed its prizes upon Bong’s non-English film—a ceremony he described as “very local”—they then named Youn Yuh-jung as Best Supporting Actress for her role in Minari, the story of a Korean immigrant family. “As the first ever film in a language other than English to win the Best Picture Oscar, among countless other prizes, Parasite became a watershed work that has opened the doors in the West for the appreciation of stories told in other tongues and about non-White people,” film critic Carlos Aguilar observes. He also underlines the importance of Korean films, casts and crews finding recognition at awards ceremonies, pointing out how Parasite was stopped short of receiving any nominations for the actors and therefore showing that “white voters are willing to celebrate Asian films but not Asian actors, [but] with Minari, that long-standing dismissal is beginning to change.” Korean films are fully realized works of art at the same time that they’re entertaining pieces of popular culture attuned to current trends; for those who need to prove where awards ceremonies currently stand through their choice of nominees and winners, Korean cinema is the most attractive option: an entire world of films with political merit and substantial brand value in the global film industry.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.