British rock band Genesis made headlines recently when they took top place in US magazine Forbes’ list of the highest-paid entertainers in the world during 2022. It makes sense to think it would be contemporary pop stars who make the most money, and historical lists certainly show that to be the case for the most part. In 2019, it was Taylor Swift, Kayne West and Ed Sheeran topping the list; for 2020, Kanye, Elton John and Ariana Grande came out on top. These rankings fluctuate by the year, and musicians in particular have seen a significant increase to their profits following a lot of successful grand-scale tours.

What about Genesis, then? The band has secured a position in music history but it’s already been 40 years since they were at the peak of their commercial success. It’s not that they put on any major concerts lately; rather, the reason for their payday is that they sold the copyrights to their music. This trend became noticeable in rankings compiled starting in 2021: For 2020, Bruce Springsteen earned $435 million off a similar sale, Paul Simon made $200 million and Bob Dylan raked in $130 million. But what exactly does it mean when a musician sells off their copyrights? And why is it worth so much? And why did it start becoming such a big thing from 2021?

First, let’s briefly explain what we mean when we’re talking about the nebulous idea of copyright. Music rights are divided into two categories: musical works and sound recordings. The songwriters, artists and record companies each retain an agreed-upon percentage of both. The profit earned off albums, downloads, streams, use in other media (sync rights) and more are divided among them. When an artist agrees to a copyright sale, or catalog sale, they transfer their portion of the right to future profits in exchange for a one-time payout.

The market for catalog sales has grown rapidly since 2020. The market went from $40 million in 2019, to $190 million in 2020, and skyrocketed to $530 million in 2021 (Larry Miller, How Streaming Has Impacted the Value of Music, New York University). There are a number of reasons behind this. First, with the maturing of the streaming market, the value of music as an asset to turn a profit became clear. Look at how it used to work: Albums don’t go on to have steady sales for long. They can’t keep their figures up forever and many factors, including the artist’s health, have a further impact. It’s also hard to predict when a song might be used in a TV show or movie and how much of a hit it might become when it is.

But streaming has proven to be different. Since 2017, streaming’s been the single biggest source of revenue in the global music market. In the five years following, profits from streaming nearly tripled, growing to account for 65% of the entire industry (International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, Global Music Report 2022). The most unique thing about streaming is that old songs continue to receive plays and therefore lead to profit. According to Billboard, so-called catalog music—songs that were released 18 months ago or longer—has steadily taken up a greater proportion of all songs streamed, reaching 72.4% in the first half of 2022. This has changed the long-term sales structure of the music industry. In the first year or two after new music is released, most of the profits come from album sales, digital downloads and radio play. But after about three years, streams become responsible for the majority of the profits, and they continue to make money fairly uniformly over time.

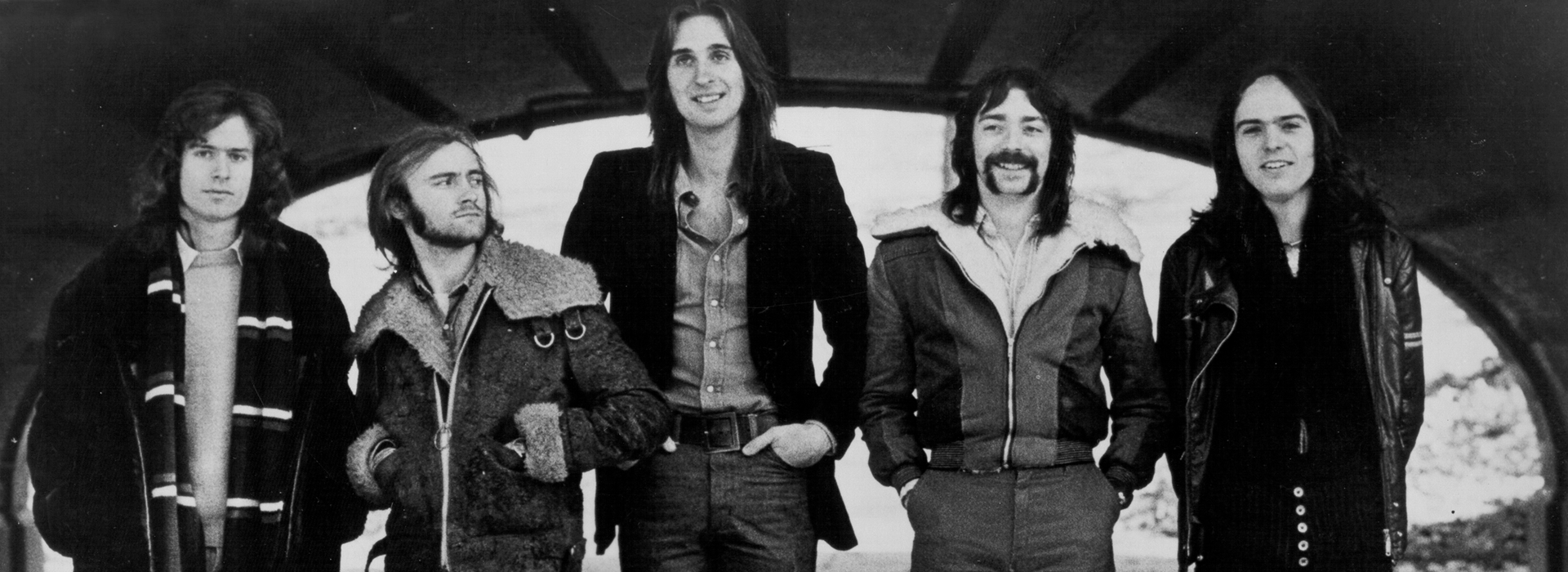

-

© Artistic Echoes

© Artistic Echoes

This is all backed by real data collected over the past five years as streaming has grown in popularity. In other words, streaming remains a reliable revenue stream well into the future. That is to say, music has become profitable in a way comparable to interest earned on bonds or dividends from stocks, meaning it can be bought and sold as an asset. COVID-19 played a major part in this change, too. Streaming rapidly became an even bigger market during the pandemic. For those looking for a stable return on investment, music became an attractive venture—an asset little swayed by fluctuations in the economy, corporate outlook or any other external force. With interest rates as low as they were, music as an asset promised better returns than bonds could. Unlike the stock market, corporate decisions have no influence on their ability to generate wealth. Income from copyright is even legally protected. Consequently, in addition to traditional players like record companies and investment companies like Hipgnosis that specialize in copyright, major investment companies like BlackRock got into the market as well.

There’s many reasons for artists to sell, too. When the pandemic prevented them from performing, catalog sales gave artists an opportunity to turn a large profit in an instant. Low interest rates also create a favorable environment for those looking to sell catalogs at a profit. The factors that go into determining those prices vary but the idea is roughly the same as with bonds: Assuming an unchanged outlook on future returns, the price goes up when the interest rate is low. Moreover, the legendary artists of the 1960s and ’70s are no longer at the point in their lives where they can perform and may be thinking about questions like inheritance. At the same time, their music has proven to command steady demand over the decades. That’s why so-called reliable catalogs from artists like Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen and, after his death, David Bowie, fetched absolute fortunes.

Interest from the market naturally extends to the younger generation as well. Justin Bieber reportedly sold his catalog for $200 million late last year. Dr. Dre also cleaned up with $200 million or more in January. The list, which includes names like Justin Timberlake and Future, is too long to be anything but unwieldy. And it’s not just artists—songwriters and producers are selling their shares of copyrights, too. In addition to streaming profits, the types of rights and the conditions attached to them are becoming extremely diverse, including rights to use the songs in other media like advertisements, trademarks on names, merchandising rights and more. And it’s not just large sales. Someone can make some cash by making a deal with an expiration date and not have to give up their rights wholesale. For example, Evanescence earned $700,000 back in 2003 when they handed over the copyright to their album Fallen for a period of 30 years.

Some expect the market to cool down from this year as interest rates rise and artists are able to perform in concert again, but other analysts point out that the streaming market is as strong as ever despite the end of the pandemic and so there will be no impact on the value of the catalogs. Still others predict headline-grabbing sales with high sticker prices are inevitable and will keep interest in the market alive. Notable artists like Pink Floyd, Queen and Billy Joel haven’t made a sale yet, after all. There were also murmurs not long back about Michael Jackson’s catalog. If the deal goes through, it will be the largest to date. Sales of music catalogs large and small are very likely to remain a strategic investment for the time being.

Because the art that makes up the music industry is so pure, it makes musicians special but complicated people. For a long time, an artist’s music was considered an achievement and their legacy. Now it’s as though every musician is running their own start-up in the world of streaming: They can sell their stake and exit. The way we listen isn’t the only thing streaming changed about music.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.