FEATURE

K-food for all!

Like BTS, the K is more than just a letter

2021.03.31

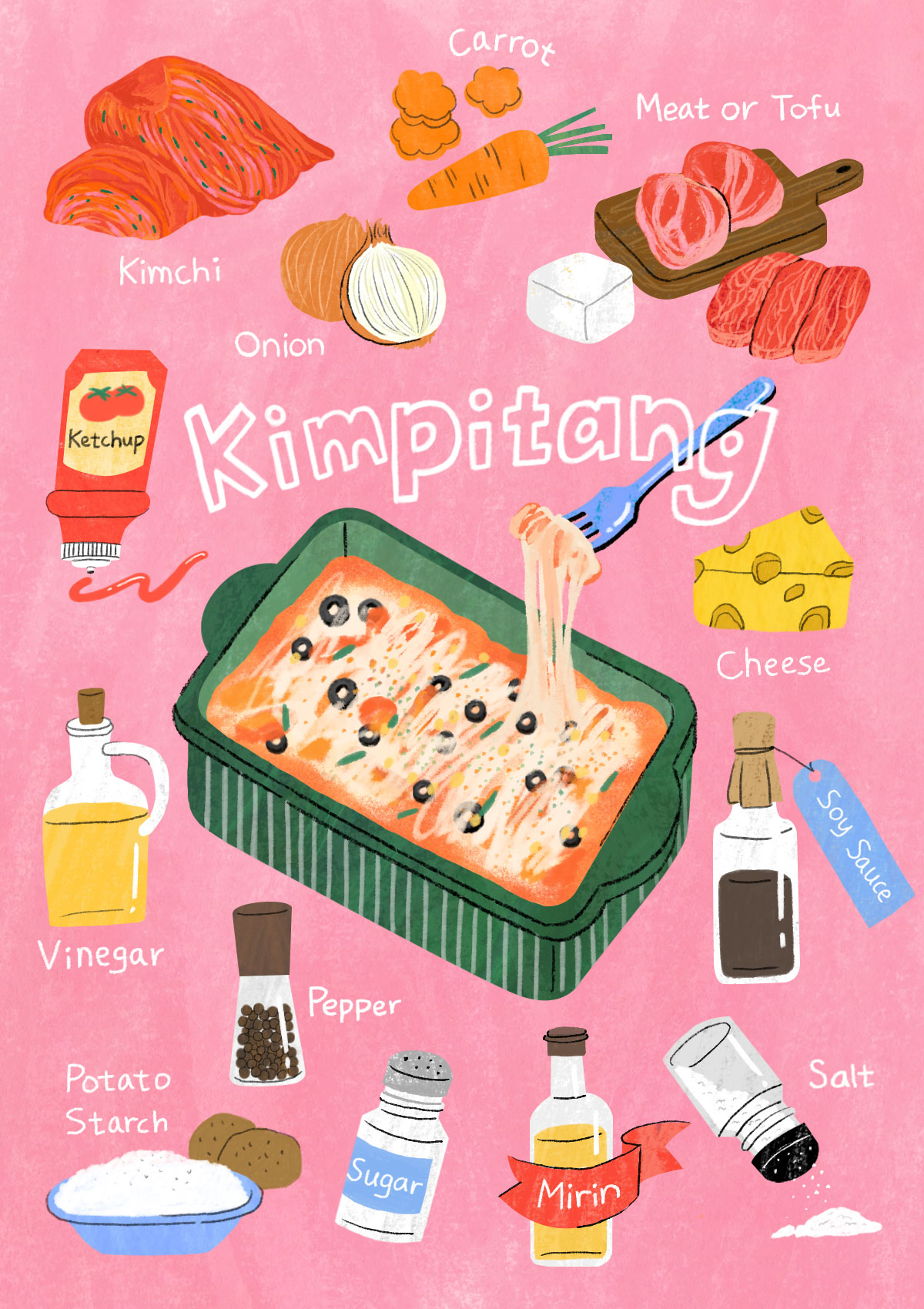

“How did they think to put these together?” asked BTS member RM while eating jjapaguri on their reality show, In the SOOP. Jjapaguri, a dish which received global recognition under the name “ram-don” in the movie Parasite, is a spicy twist on jjajangmyeon (black bean noodles) made by mixing Chapagetti and Neoguri, two Korean instant noodle brands. BTS’s original series, RUN BTS, often spotlights foods that leave viewers asking questions not unlike RM’s. Consider kimpitang, which is tangsuyuk or sweet and sour pork covered with Italian pizza toppings and kimchi; kkakdugi fried rice with cheese, a typical side menu at Korean barbecue restaurants; or sundingi ramyeon, made from Korean spam and sausages mixed into instant noodles: They are all fusion dishes made from mixing Korean food with ingredients from other countries, or else once-rarely-seen local concoctions. The 125th episode of RUN BTS, aired in January, was titled “K-HAM Special.” Spam, first introduced by Hormel Foods Corporation in the United States in 1937, has long been eaten in Korea with foods like kimchi and rice as a side dish. Ingredients once unheard of in Korean cuisine have gained a foothold in modern times, padding out a menu that defies nationality.

“Mozzarella cheese is a very important ingredient in Korean food right now.” So said chef and food columnist Park Chan-il, who cooks at Korean restaurant Gwanghwamun Gukbap and the Italian-style Locanda Mong-Ro, the former of which has been awarded a MICHELIN Bib Gourmand three years running. With his hands in both the Korean and Western food fields, his statement was symbolic: “Most of the Korean food that the younger generation of Koreans likes has cheese in it. Dakgalbi or chicken stir-fry, kimchi jjigae, fried rice—there are many instances of cheese being used in Korean food lately,” he said. “When it comes to Korean food, the origin of the ingredients isn’t important anymore.” He also pointed out how “the idea to powder Korean chicken before frying it may have come from KFC in the States, but the innovative American Modernist Cuisine team, that marries cooking with science, even refers to the sweet and spicy kind as Korean-style fried chicken.” In other words, this originally American food crossed over to Korea, gained a new footing with a unique approach, and then this custom take returned home to find its own place in the market. Similarly, places abroad are adding their own local spin on traditional Korean food. One example is “quick kimchi,” which The New York Times introduced as a faster recipe for kimchi, foregoing the need to ferment anything, and coming out similar to muchim. “One of the defining criteria of Korean kimchi according to the Codex international food standards body is the stage of lactic acid fermentation at low temperatures,” Misiguibyeol, a food critic who writes under the username maindish1, said about such nonstandard kimchi preparations consumed internationally. “It’s the same phenomenon where Mexican cuisine entered the American South and became Tex-Mex, then Koreans put kimchi on top of that to create kimchi tacos,” or K-Tex-Mex. “The original has to be respected, but I think the more all these food cultures give and take from one another, the more culture we can enjoy.”

The actual phenomenon of transforming foreign food to bring it in line with the culture and conditions of its adoptive country has been universal from the start. As an example, while budaejjigae is considered Korean cuisine, the dish was created using American spam when it was first introduced to the country after the Korean War of 1950. Park believes “the growth of media, especially the ubiquity of YouTube and smartphones,” has accelerated the fusing and localizing of foods more than ever. Fusion foods such as kimpitang, chicken in Toowoomba sauce and fat macarons (or “fatcarons”—a type of K-macaron with a very thick filling) have made waves in recent years. “We’re in an era where you can read the New York Times editorial in Korea,” said Park. “The younger generation is relatively comfortable with using English, and have been exposed to Western food from an early age, and they embrace other cultures both head on and indirectly, so they’re not scared to try new ingredients.” He sees “mixing all sorts of different ingredients to make ‘peculiar food’ ” as a “means of self-expression. It doesn’t even have to taste good, so long as it’s fun to look at. Food is already in the realm of entertainment.”

“Mozzarella cheese is a very important ingredient in Korean food right now.” So said chef and food columnist Park Chan-il, who cooks at Korean restaurant Gwanghwamun Gukbap and the Italian-style Locanda Mong-Ro, the former of which has been awarded a MICHELIN Bib Gourmand three years running. With his hands in both the Korean and Western food fields, his statement was symbolic: “Most of the Korean food that the younger generation of Koreans likes has cheese in it. Dakgalbi or chicken stir-fry, kimchi jjigae, fried rice—there are many instances of cheese being used in Korean food lately,” he said. “When it comes to Korean food, the origin of the ingredients isn’t important anymore.” He also pointed out how “the idea to powder Korean chicken before frying it may have come from KFC in the States, but the innovative American Modernist Cuisine team, that marries cooking with science, even refers to the sweet and spicy kind as Korean-style fried chicken.” In other words, this originally American food crossed over to Korea, gained a new footing with a unique approach, and then this custom take returned home to find its own place in the market. Similarly, places abroad are adding their own local spin on traditional Korean food. One example is “quick kimchi,” which The New York Times introduced as a faster recipe for kimchi, foregoing the need to ferment anything, and coming out similar to muchim. “One of the defining criteria of Korean kimchi according to the Codex international food standards body is the stage of lactic acid fermentation at low temperatures,” Misiguibyeol, a food critic who writes under the username maindish1, said about such nonstandard kimchi preparations consumed internationally. “It’s the same phenomenon where Mexican cuisine entered the American South and became Tex-Mex, then Koreans put kimchi on top of that to create kimchi tacos,” or K-Tex-Mex. “The original has to be respected, but I think the more all these food cultures give and take from one another, the more culture we can enjoy.”

The actual phenomenon of transforming foreign food to bring it in line with the culture and conditions of its adoptive country has been universal from the start. As an example, while budaejjigae is considered Korean cuisine, the dish was created using American spam when it was first introduced to the country after the Korean War of 1950. Park believes “the growth of media, especially the ubiquity of YouTube and smartphones,” has accelerated the fusing and localizing of foods more than ever. Fusion foods such as kimpitang, chicken in Toowoomba sauce and fat macarons (or “fatcarons”—a type of K-macaron with a very thick filling) have made waves in recent years. “We’re in an era where you can read the New York Times editorial in Korea,” said Park. “The younger generation is relatively comfortable with using English, and have been exposed to Western food from an early age, and they embrace other cultures both head on and indirectly, so they’re not scared to try new ingredients.” He sees “mixing all sorts of different ingredients to make ‘peculiar food’ ” as a “means of self-expression. It doesn’t even have to taste good, so long as it’s fun to look at. Food is already in the realm of entertainment.”

With 40 thousand followers on Twitter, the BTS ARMY Kitchen team is one such example of how modern media can fashion entertainment from global food culture. The team, “composed of highly-qualified professional chefs, talented home cooks, spectacular bartenders, and passionate bakers,” and ARMY, invent recipes connected to BTS and share them with members of BTS’s ARMY fan base via social media. They say that their “ultimate goal is to foster a place that people can connect through food and conversation,” and have held events where they give some recipes for snacks that ARMYs can enjoy during BTS’s online concerts, like BANG BANG CON The Live and MAP OF THE SOUL ON:E. They also organize events like #BTSSoupWeek, which introduced BTS fans to dishes from various countries the musicians visited while on tour, and shared their own recipes for traditional Korean foods—including tteokguk (rice cake soup), sujeonggwa (cinnamon punch), yakgwa (honey cookies), and jeon (savory pancakes)—to celebrate Korean New Year with BTS. According to the BTS ARMY Kitchen team, “When these kinds of events happen, we’ll ask ourselves, ‘What would be fun to have ARMY try?’ and then we go from there.”

For people all across the world, this concept of using food as a communication medium is now, as it is for ARMY, one method of connecting with one another’s cultures. The BTS ARMY Kitchen team takes diversity into account: They provide ARMY with vegan recipes for Korean dishes like tteokguk and cockle bibimbap (mixed rice), and spotlighted a halal kombucha that caught the team’s attention when Jung Kook was seen drinking it. “We have always been adamant about being inclusive and respectful of ARMY from all walks of life, their preference, lifestyles and/or religion,” the team said. “We take special care to always keep in mind that not all of us can have or eat what BTS ate, but we can try and replicate it to the best of our abilities so they can experience it as well.” The team also revealed that “a problem that many international ARMY have when cooking Korean dishes” is that “they may not be able to get certain ingredients that are vital to a dish. In that case we have to come up with accessible replacements that won’t alter the taste of the dish.”

The fact that Korean cuisine is recognized around the world as a potential vegan and health food is interesting because it reflects a global trend toward respecting cultural diversity and everyone’s individual dietary requirements. “I know that people overseas have been showing interest in Korean temple food,” Park said, “because it contains elements of vegan food.” According to Misiguibyeol, “It’s easy to come up with vegan recipes for Korean food like kimchi, bibimbap, jeon, jjigae, and japchae (stir-fried glass noodles),” calling this “Korean food’s power to keep up with the changing times.” One notable food that showcases the importance of cultural diversity is CJ CheilJedang’s Bibigo brand mandu. As of December 2019, Bibigo mandu exceeded one trillion won in annual sales of which 65% are from exports to 15 countries including the US, China, Japan and Germany. “Mandu is similar to other ubiquitous wrapped foods like tacos, gyoza and dumplings, so people around the world had no trouble welcoming them into their diets,” a representative for CJ CheilJedang said. “Bibigo mandu are tightly stuffed with fillings like meat and vegetables and wrapped in thin dough and so have come to be recognized as healthy food. At the same time, we have benefited from launching localized versions, like a coriander and chicken version that suits some local tastes,” citing this as one of the keys to their success. A new market is unfolding for Korea as it once again develops food products aimed at the individual tastes of varying cultures and the world as a whole discovers the unique charm of Korean cuisine.

For people all across the world, this concept of using food as a communication medium is now, as it is for ARMY, one method of connecting with one another’s cultures. The BTS ARMY Kitchen team takes diversity into account: They provide ARMY with vegan recipes for Korean dishes like tteokguk and cockle bibimbap (mixed rice), and spotlighted a halal kombucha that caught the team’s attention when Jung Kook was seen drinking it. “We have always been adamant about being inclusive and respectful of ARMY from all walks of life, their preference, lifestyles and/or religion,” the team said. “We take special care to always keep in mind that not all of us can have or eat what BTS ate, but we can try and replicate it to the best of our abilities so they can experience it as well.” The team also revealed that “a problem that many international ARMY have when cooking Korean dishes” is that “they may not be able to get certain ingredients that are vital to a dish. In that case we have to come up with accessible replacements that won’t alter the taste of the dish.”

The fact that Korean cuisine is recognized around the world as a potential vegan and health food is interesting because it reflects a global trend toward respecting cultural diversity and everyone’s individual dietary requirements. “I know that people overseas have been showing interest in Korean temple food,” Park said, “because it contains elements of vegan food.” According to Misiguibyeol, “It’s easy to come up with vegan recipes for Korean food like kimchi, bibimbap, jeon, jjigae, and japchae (stir-fried glass noodles),” calling this “Korean food’s power to keep up with the changing times.” One notable food that showcases the importance of cultural diversity is CJ CheilJedang’s Bibigo brand mandu. As of December 2019, Bibigo mandu exceeded one trillion won in annual sales of which 65% are from exports to 15 countries including the US, China, Japan and Germany. “Mandu is similar to other ubiquitous wrapped foods like tacos, gyoza and dumplings, so people around the world had no trouble welcoming them into their diets,” a representative for CJ CheilJedang said. “Bibigo mandu are tightly stuffed with fillings like meat and vegetables and wrapped in thin dough and so have come to be recognized as healthy food. At the same time, we have benefited from launching localized versions, like a coriander and chicken version that suits some local tastes,” citing this as one of the keys to their success. A new market is unfolding for Korea as it once again develops food products aimed at the individual tastes of varying cultures and the world as a whole discovers the unique charm of Korean cuisine.

Whether it is products like Bibigo or foods that BTS are enjoying, we witness the phenomenon of these flavors spreading through media to different cultures around the world, where they are then embraced in novel ways. And so, like the cuisines of other countries before it, Korean food, or “K-food” as it is also known lately, has taken on a different meaning. The BTS ARMY Kitchen team pointed to “the great versatility an ingredient can have to be used in many dishes” as a specialty of Korean cooking. “That’s something BTS, their music, and Korean cuisine have in common. They are so versatile with their different musical styles and concepts, that you get so much diversity from one band.” BTS has put out global hits encompassing such diverse genres as hip hop, rock, EDM, Korean traditional music and more. Meanwhile, Korea has gained a reputation for its extremely spicy food, as evidenced by the viral Fire Noodle Challenge on YouTube, where people challenge themselves to eat buldak, or hot chicken, flavored noodles, the sauce for which, while produced in Korea since the early 2000s, was itself inspired by American hot sauce (Ju Yeongha, One Hundred Years of Food). It is telling that Misiguibyeol considers one main feature of widely popular Korean dishes to be their absence of cohesive nationality: “Korea is good at creating food with mass appeal. There’s a lot of fusion foods that have nothing to do with traditional Korean food. A prime example is mango cheese bingsu: While the Korean bingsu chain Sulbing took a cue from Taiwanese shaved ice, they created mango cheese bingsu with cheese, which wasn’t a bingsu topping before but grew to be popular.” In short, the K in K-food does not necessarily signal the presence of ingredients from traditional Korean food. In 2021, we are already witnessing never-before-seen creations synthesized from a jumble of different cultures, and thanks to the media they are sprouting up anew in different places, only to take on lives of their own. And the K in K-food is a part of that trend.

As Korean cuisine brushes past more and more foods abroad, the meaning behind the K prefix is fading, and as media continue to develop, we are witnessing a sensation of cultures mixing and matching as international borders consequently lose their meaning. The BTS ARMY Kitchen team say they “are driven by the importance of communication through cultural exchange and cultural competence*.” In an era where cultural exchange has become a form of entertainment in itself, their words serve as a bellwether of where to head with Korea’s many K-prefixed cultural assets. “Learning and being more aware of how we can respect each other will allow us to close the gaps in disagreements, learn different perspectives, challenge biased thinking, and decrease stereotypes. This is needed more than ever as the world is going through a mental health crisis, a greater socio-economic divide, oppression, and racial injustice.” From such a global perspective, the meaning behind the K prefix can be reinterpreted. It represents our era in which cross-border cultural amalgamation happens routinely in Korea and is in turn localized liberally by others around the world. At the same time, it is a keyword that shows all we have to sit down and ponder. But if there were one word that could sum up K and everything it stands for, it’s safe to say that word would be NOW.

*To be culturally competent is to be aware of cultural diversity while making an effort to better meet the needs of minorities by expanding one’s cultural knowledge and breadth of resources through persistent self-reflection.

As Korean cuisine brushes past more and more foods abroad, the meaning behind the K prefix is fading, and as media continue to develop, we are witnessing a sensation of cultures mixing and matching as international borders consequently lose their meaning. The BTS ARMY Kitchen team say they “are driven by the importance of communication through cultural exchange and cultural competence*.” In an era where cultural exchange has become a form of entertainment in itself, their words serve as a bellwether of where to head with Korea’s many K-prefixed cultural assets. “Learning and being more aware of how we can respect each other will allow us to close the gaps in disagreements, learn different perspectives, challenge biased thinking, and decrease stereotypes. This is needed more than ever as the world is going through a mental health crisis, a greater socio-economic divide, oppression, and racial injustice.” From such a global perspective, the meaning behind the K prefix can be reinterpreted. It represents our era in which cross-border cultural amalgamation happens routinely in Korea and is in turn localized liberally by others around the world. At the same time, it is a keyword that shows all we have to sit down and ponder. But if there were one word that could sum up K and everything it stands for, it’s safe to say that word would be NOW.

*To be culturally competent is to be aware of cultural diversity while making an effort to better meet the needs of minorities by expanding one’s cultural knowledge and breadth of resources through persistent self-reflection.

Article. Rieun Kim

Design. Eomji(instagram @andeomji / eomji_illust@naver.com)

Visual Director. Yurim Jeon

Review. Chanil Park(Food Columnist)

Copyright © Weverse Magazine. All rights reserved.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.

Read More