FEATURE

Getting to know Korean modern and contemporary art with RM

Take a look at the musician’s top artists

2021.03.24

Even when you only have a passing interest in something, if you do it together with someone else, you can feel the anticipation from head to toe. You cannot help but sense some togetherness, even if you are in different places, when they share their thoughts and feelings—the conversations during this particularly intimate time bring you a little closer to this person who seems far away.

RM, the leader of BTS, is quick to show off his love of and fond eye for art. He does not stop at merely talking about artists and artwork he admires; he shares this affection with many people by donating to art-related causes, and it is all possible because he is so enamored with the pleasure that art has to offer. RM says he feels rested and inspired after viewing art, which in turn makes us more curious about the arts as well.

What does the world of art look like through RM’s eyes? Art critic Jangro Lee explores this question by going into detail about the artists and artworks in which the musician is most interested.

RM, the leader of BTS, is quick to show off his love of and fond eye for art. He does not stop at merely talking about artists and artwork he admires; he shares this affection with many people by donating to art-related causes, and it is all possible because he is so enamored with the pleasure that art has to offer. RM says he feels rested and inspired after viewing art, which in turn makes us more curious about the arts as well.

What does the world of art look like through RM’s eyes? Art critic Jangro Lee explores this question by going into detail about the artists and artworks in which the musician is most interested.

Kim Whanki

Artists and the general public now have more opportunities to communicate through various media, and so, in addition to their work, fans are also paying attention to artists’ actions. Such is the case for a photo of RM standing with Eternal Song, one of Kim Whanki’s works, when it was shown at an exhibition held at the Seoul Museum of Art.

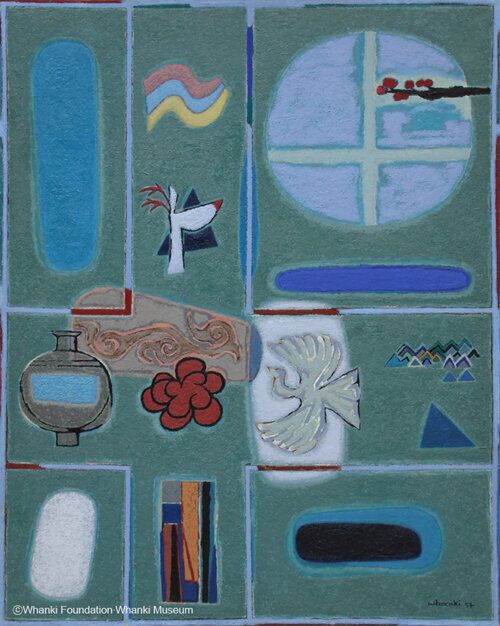

Eternal Song

Could an artist envision a more shining way to say they want to be with us forever? While studying in Paris, Kim painted this modern take on the Korean aesthetic, a work which is not unlike a fan’s desire for their favorite artist to keep at their craft for a long time.

Artists and the general public now have more opportunities to communicate through various media, and so, in addition to their work, fans are also paying attention to artists’ actions. Such is the case for a photo of RM standing with Eternal Song, one of Kim Whanki’s works, when it was shown at an exhibition held at the Seoul Museum of Art.

Eternal Song

Could an artist envision a more shining way to say they want to be with us forever? While studying in Paris, Kim painted this modern take on the Korean aesthetic, a work which is not unlike a fan’s desire for their favorite artist to keep at their craft for a long time.

-

Kim Whanki, Eternal Song. 1957. © Whanki Foundation and Whanki Museum.

Kim Whanki, Eternal Song. 1957. © Whanki Foundation and Whanki Museum.

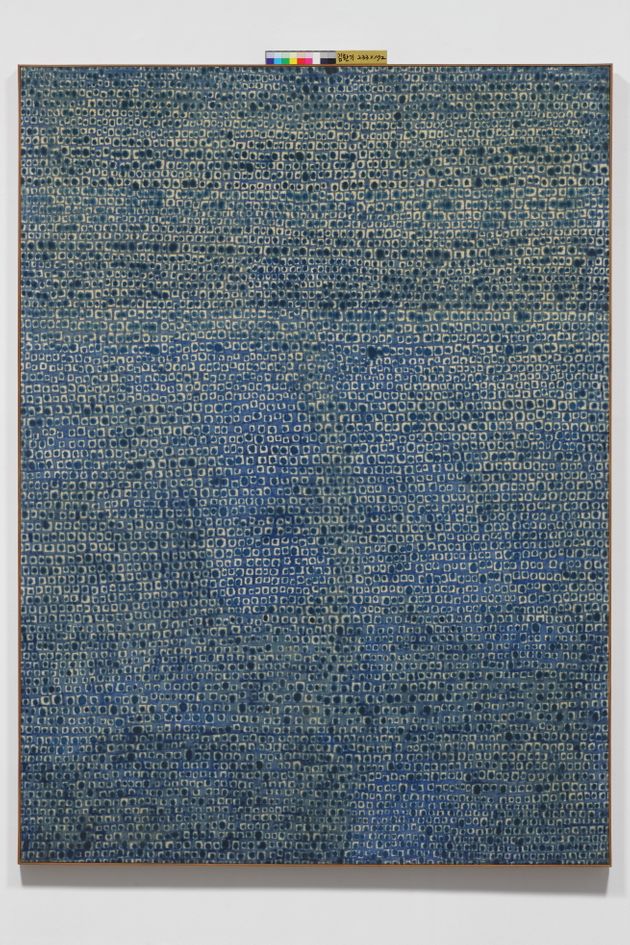

Kim makes frequent use of naturalistic motifs in this work and images that he feels best reveal Korean emotions, and the thick brushstrokes on the canvas maximize the impact of the texture, a characteristic notable in works of the Paris art scene at the time. Kim concentrated during this period of his life on producing works which feel poetically Korean while at the same time exchanging ideas with his better-known contemporaries. He described the unique qualities found in their masterpieces as being akin to their own powerful songs, and so was in essence seeking to write his own. When seen from this perspective, Eternal Song feels all the more significant. Images like birds, mountains, deer, clouds, ceramics and more symbolize the immortality of nature and tradition; as songs have long been regarded as poems with sound, Kim shows on his canvas the formative language in which imagery-rich poems are written. The disciplined technique and harmonious use of color, embodied by the flat composition and simplified form, characterize this work, one considered to fully capture Kim’s views and identity as a fine artist and literary writer. However, Kim’s style did not stop evolving here; after some time in New York, he pressed onward to create his widely recognized series of full-canvas dot paintings. He makes use of repeated points, or dots, as a basic structure, but the lines surrounding the dots on Kim’s canvases and the repeated changes in their color is wholly original. One of his most famous series of paintings, Where, in What Form, Shall We Meet Again?, which derives its name from the final line of a poem by Kim Kwang-seop titled “In the Evening,” is filled with an impressive display of these blue points, which in turn represent the artist’s thoughts about and longing for his home country. The points are not cleanly dabbed on but watered down and smeared, covering the canvas in different shades of blue. The points smudge and spread, meeting each other and extending from a number of solitary elements into an open and expanded shape to demonstrate the harmony of moderation and magnificence. With these techniques showing the differences in his methods but consistent use of Korean motifs and naturalism, Kim’s works will stand forever as eternal songs.

-

Kim Whanki, Where, in What Form, Shall We Meet Again? 1970. © Whanki Foundation and Whanki Museum.

Kim Whanki, Where, in What Form, Shall We Meet Again? 1970. © Whanki Foundation and Whanki Museum.

Lee Ungno

Korean modern art began in the era of the artist and continues even today. The driving force that keeps the current moving despite the nation’s exhausting history are the artists who create within its scope and constantly push for change, and therefore the world shown in these artists’ work is, without exception, a projection based in the reality of the world they have experienced.

Korean modern art began in the era of the artist and continues even today. The driving force that keeps the current moving despite the nation’s exhausting history are the artists who create within its scope and constantly push for change, and therefore the world shown in these artists’ work is, without exception, a projection based in the reality of the world they have experienced.

-

Lee Ungno, Bamboo. 1971. © Lee Ungno Museum.

Lee Ungno, Bamboo. 1971. © Lee Ungno Museum.

RM posted a picture of Lee Ungno’s Bamboo online, telling his fans that he visited the exhibit called The Square: Art and Society 1900–2019 at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. RM also showed off his love of art by highlighting the People series and pointing out that it is a later work by the same artist. Lee’s artwork is particularly interesting when reviewed chronologically, as doing so emphasizes his change in style. His early works were of the so-called four gracious plants in ink which established him firmly within the field of Korean traditional art. Lee had a deep interest in and affection for bamboo: He is said to have made paintings of bamboo exclusively for the seven years following his win at the Joseon Art Exhibition in 1924. Bamboo in art is traditionally associated with noblemen, suggesting straight thinking and integrity. Lee’s mastery as a mukjukhwa, or bamboo in ink painter that he had been fostering since his youth is clearly apparent in Bamboo, Lee’s 1971 painting which RM posted. The bamboo is realistically expressed with variations in ink saturation on screens reaching three meters tall and welcomes audiences into what feels like a genuine bamboo forest. Lee’s work during this period is particularly vibrant and he emphasizes the bamboo’s leaves as well as variations in the joints more expressively than before. While these works remain within the mukjukhwa genre, we can see the changes to Lee’s style over time. In his later years, Lee went on to create the now-familiar People series that shows a crowd of humanlike figures painted with brushstrokes reminiscent of calligraphy. The figures in the paintings seem to run off in one direction, as if the elderly Lee were expressing the vitality of the human spirit beyond the realm of history and civilization.

-

Lee Ungno, People. 1988. Image courtesy SmartK.

Lee Ungno, People. 1988. Image courtesy SmartK.

Yun Hyong-keun

As we have seen, it is only natural for an artist’s character—that is, their spirit and attitude toward life—to be embedded in their work. This sense of character and the images it produces is the chief force behind our ability to enjoy the artwork, allowing ourselves to be immersed in deep fascination as we view them. From what we have seen, RM is drawn to and intrigued by Yun Hyong-keun’s art, having visited exhibitions in Seoul as well as in Venice and New York while traveling. This is not an easy feat without passion, which makes it easy to see the interest in and affection that RM has for Yun and his work.

As we have seen, it is only natural for an artist’s character—that is, their spirit and attitude toward life—to be embedded in their work. This sense of character and the images it produces is the chief force behind our ability to enjoy the artwork, allowing ourselves to be immersed in deep fascination as we view them. From what we have seen, RM is drawn to and intrigued by Yun Hyong-keun’s art, having visited exhibitions in Seoul as well as in Venice and New York while traveling. This is not an easy feat without passion, which makes it easy to see the interest in and affection that RM has for Yun and his work.

-

Yun Hyong-keun, untitled. C. 1966. Image courtesy Muum.

Yun Hyong-keun, untitled. C. 1966. Image courtesy Muum.

Yun’s works, which, as RM enthusiastically notes, differ depending on how old the artist was when he painted any particular one, and he is best known for his dansaekhwa, or monochrome painting , but the early works painted in his youth are bright abstracts. The lyrical sentimentality of his early work seems to have been a reflection of mentor and father-in-law Kim Whanki’s influence on Yun, but following a false accusation of violating anticommunist laws and his subsequent release from prison, Yun’s work took on the darker atmosphere and colors with which we most readily associate him today. Observers are invariably left with an intense impression of the resentment and sorrow which anguished Yun when they look at the black columns on his canvas. The shade of black, reminiscent of ink , was not actually created using black paint, but as a result of the layers of burnt umber (deep red) and ultramarine (deep blue) Yun repeatedly applied to the canvas. The paints are layered onto the glue-primed canvas so that the colors run freely, displaying the various colors that seem to spread out unintentionally but subtly from the darkness. Likewise, the viewer can read into the complex atmospheric emotion of the vertical bands of color in his lifelong series Umber-Blue as they mingle with the white space of the outer margins. Because the colors and margins of the works vary by the era and situation in which each was painted, full immersion in a given work comes from a proper analysis of Yun’s environment and thought process at the time he was painting.

-

Yun Hyong-keun, Umber-Blue. 1973. Image courtesy National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art.

Yun Hyong-keun, Umber-Blue. 1973. Image courtesy National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art.

Kwon Dae-sup

Until this point, we have mainly discussed paintings, but they are not the only works of art that embody Korean history and traditions. That is not to suggest that works that inherit from tradition are always excluded from the list of artistic genres, but no list would be complete without the ceramics of Kwon Dae-sup. RM, who uploaded a picture of himself with one of Kwon’s moon jars in his arms on his social media, admiringly referred to Kwon as a master of Korean aesthetics while viewing his work s at an exhibition. Moons jars, a porcelain pottery originally made in the late Joseon period, are representative Korean ceramics famous for their gentle white color and curves. Although he majored in painting, Kwon became fascinated with the shape and image of moon jars and has been working as a ceramics artist ever since. It is only natural that Kwon’s moon jars—which he has been working on and perfecting for ages, and which are made using the spirit and techniques associated with traditional white porcelain—should be recognized as masterpieces ; they are a refinement of the basic moon jar form, clean and free from defects, with a minimalism well suited to modern sensibilities.

Until this point, we have mainly discussed paintings, but they are not the only works of art that embody Korean history and traditions. That is not to suggest that works that inherit from tradition are always excluded from the list of artistic genres, but no list would be complete without the ceramics of Kwon Dae-sup. RM, who uploaded a picture of himself with one of Kwon’s moon jars in his arms on his social media, admiringly referred to Kwon as a master of Korean aesthetics while viewing his work s at an exhibition. Moons jars, a porcelain pottery originally made in the late Joseon period, are representative Korean ceramics famous for their gentle white color and curves. Although he majored in painting, Kwon became fascinated with the shape and image of moon jars and has been working as a ceramics artist ever since. It is only natural that Kwon’s moon jars—which he has been working on and perfecting for ages, and which are made using the spirit and techniques associated with traditional white porcelain—should be recognized as masterpieces ; they are a refinement of the basic moon jar form, clean and free from defects, with a minimalism well suited to modern sensibilities.

-

Kwon Dae-sup, Moon Jar. Image courtesy K Auction.

Kwon Dae-sup, Moon Jar. Image courtesy K Auction.

Because large moon jars are difficult to make all in one piece, the top and bottom must be crafted separately and fused together using highly refined skills , a process that underscores the distinction between aesthetic and finish for each individual artist, with the inevitable imperfections in the round shape adding to the beauty of each jar. While always white, the fact that the artist controls how clear or cloudy the jars will be by maneuvering the fire in the kiln shows just how difficult a process it is. The understated yet warm quality of the moon jar is reflected in the unaffected sincerity of these details. This refined balance reveals Kwon’s desire to create something simple and traditional, while minute irregularities bestow each jar with a unique effervescence. In the hands of an artist with modern sensibilities, this process of creating traditional pottery like the moon jar precisely pinpoints where tradition intersects with modernity, and enriches our aesthetic experience as viewers.

Joung Young-ju

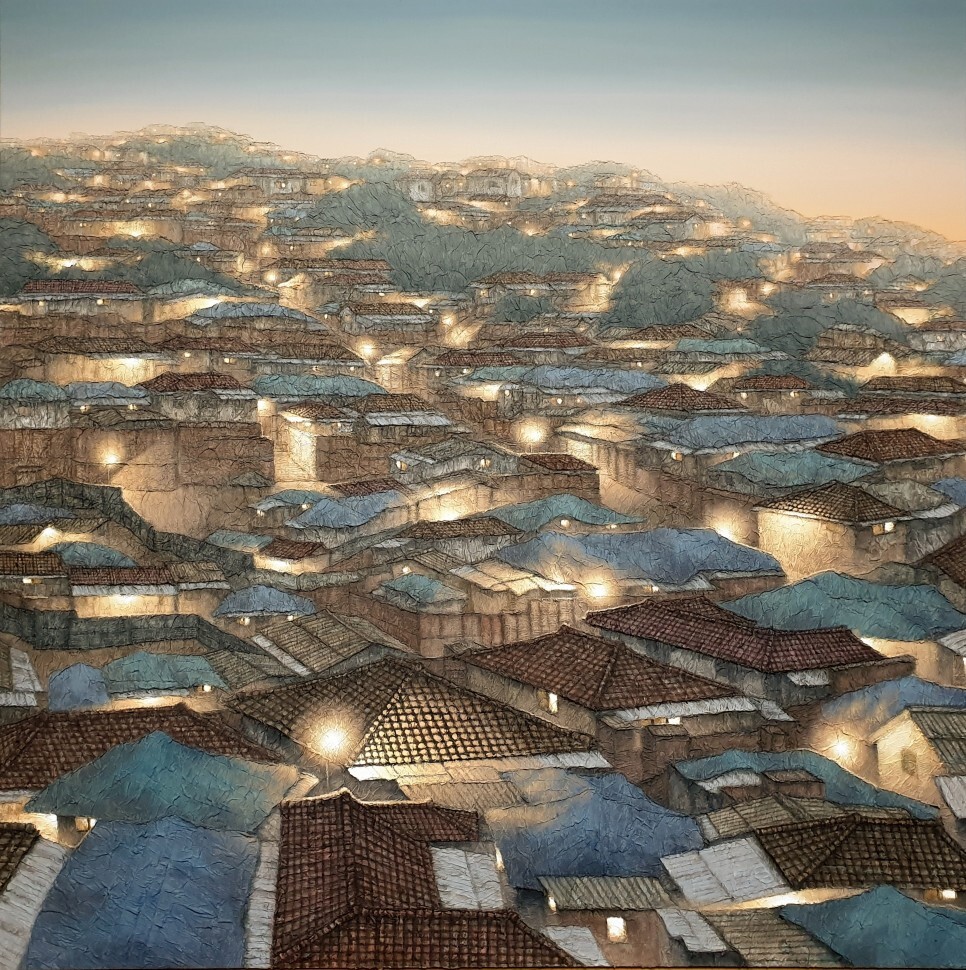

Just as we can find comfort and warmth in the traditional elements of a work, we sometimes find ourselves, although unsure as to why, longing for something when emotions from our past resurface. Perhaps that is why artist Joung Young-ju’s City, Disappearing Landscape and the emotion it stirs up feel so familiar.

Joung Young-ju

Just as we can find comfort and warmth in the traditional elements of a work, we sometimes find ourselves, although unsure as to why, longing for something when emotions from our past resurface. Perhaps that is why artist Joung Young-ju’s City, Disappearing Landscape and the emotion it stirs up feel so familiar.

-

Joung Young-ju, Disappearing Hometown 730. 2020. From the artist’s Blog.

Joung Young-ju, Disappearing Hometown 730. 2020. From the artist’s Blog.

The works in the series, which capture scenes from old shantytowns, look as realistic as a photograph would, yet are made using a technique called papier collé, which incorporates different materials affixed to a canvas. Korean traditional paper known as hanji is wrinkled and coated with acrylic paint to bring out the landscape of an old neighborhood, showing traces of time as the color and texture of the paper achieve a three-dimensional effect. True to the series name, the perspective causes the houses in Disappearing Landscape to appear blurred, in line with the theme of evoking memories of the past before everything disappears. Joung pours her personal feelings of comfort associated with a small hometown into her works so that those who view them inevitably feel a warm nostalgia regardless of whether they have even seen such sights in person or not. Interestingly, in her recreation of tender neighborhood memories, Young does not include a single person in the picture. The likely reason we feel the liveliness and nostalgia in each painting despite the absence of people is the array of brightly lit houses that fill the canvas. As is always the case, what we see at first glance is not all we are being told, and it is easy enough for us to imagine all the people in the neighborhood spending their time in their homes; our imaginations carry us into a place of lyrical memory in Joung’s works.

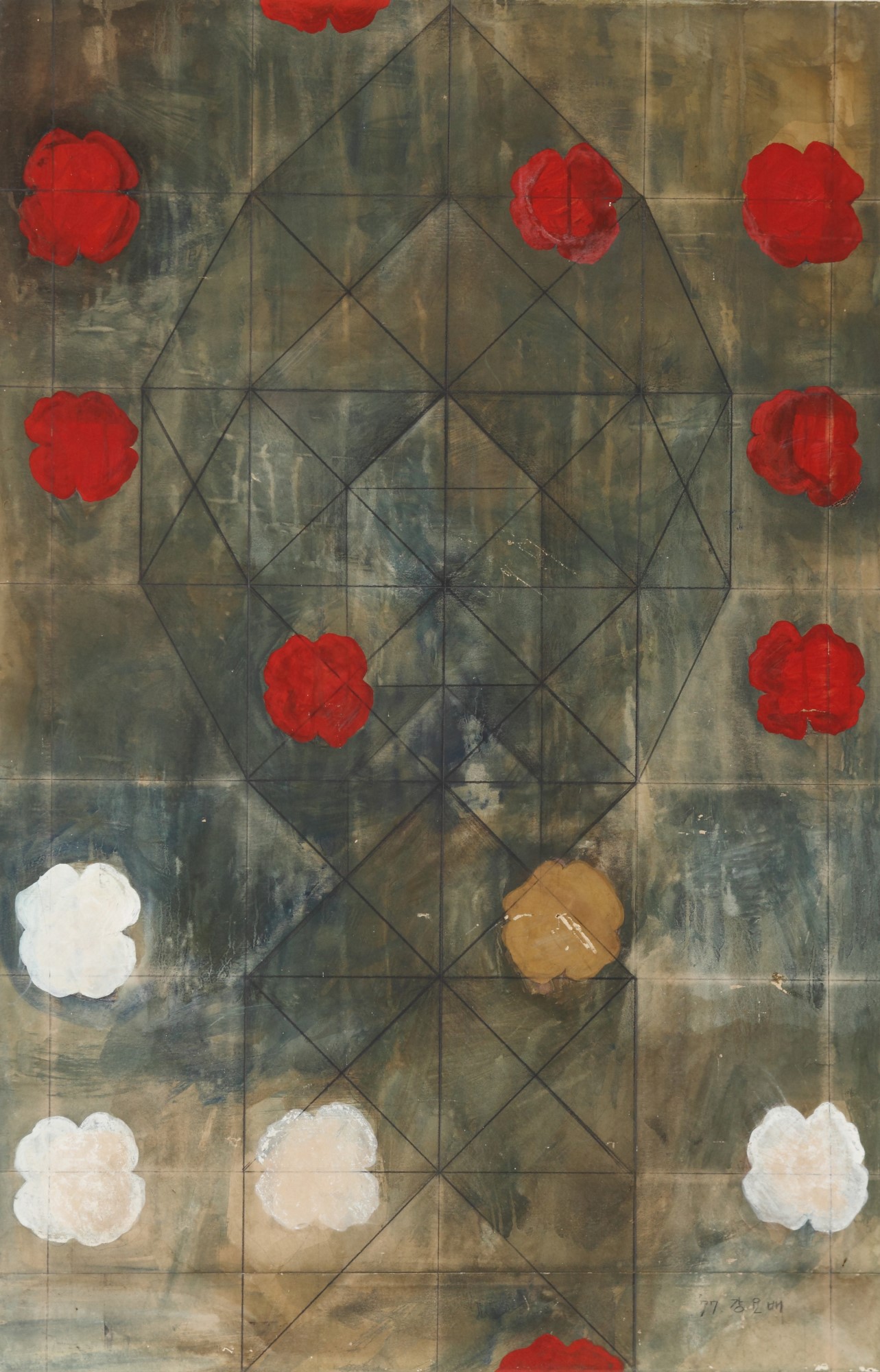

Kang Yobae

Memory and the meaning attached to it are different for everyone. The artist Kang Yobae, who was born and raised on Jeju Island, associates memory chiefly with time and place as it relates specifically to Jeju. His work focuses on the island’s nature and history.

Kang Yobae

Memory and the meaning attached to it are different for everyone. The artist Kang Yobae, who was born and raised on Jeju Island, associates memory chiefly with time and place as it relates specifically to Jeju. His work focuses on the island’s nature and history.

-

Kang Yobae, Flowers and Weapon. 1977. Image courtesy National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art.

Kang Yobae, Flowers and Weapon. 1977. Image courtesy National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art.

RM mentioned a book he has been reading recently: The Depth of Landscape, a compilation of Kang’s art alongside his personal writings that explore his life and works. The book, an inquiry into the thinking and rationale Kang has put into his art, is an intriguing read by itself, but is particularly noteworthy given how rare it is for Korean artists to write about their own work. Kang’s book opens with the line, “I was raised on the island, and I’ve come back to the island.” A prominent figure of the Minjung (“people’s”) A rt and movement of the 1980s, Kang filled his paintings with the painful but powerful memories of his hometown, and specifically of the Jeju uprising. However, many of his works shed light on the island’s natural side as well. He mixes traditional landscape paintings with Western techniques and shows all four seasons, but there is more happening on the canvas than what might be immediately apparent. Kang’s memory of the landscape is filled with life and stories, making it necessarily different from how it is seen in the eyes of the viewers . Though they look at the same sea and sky as him, Kang reconstructs the scenes through his memory of the history behind, and stories contained within them. Most notably, the wind, a common element of his work, is painted with delicate, unconstrained brushstrokes to capture the sense of time and place, and the animated environment therein. Kang’s illustrated winds stir the hearts of observers with that which his own heart has faced and his views from every moment throughout his whole life.

-

Kang Yobae, South Wind 1. 1992. Image courtesy Dolbegae Publishers.

Kang Yobae, South Wind 1. 1992. Image courtesy Dolbegae Publishers.

Article. Jangro Lee (Art Critic)

Photo Credit. BTS Twitter

Copyright © Weverse Magazine. All rights reserved.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.