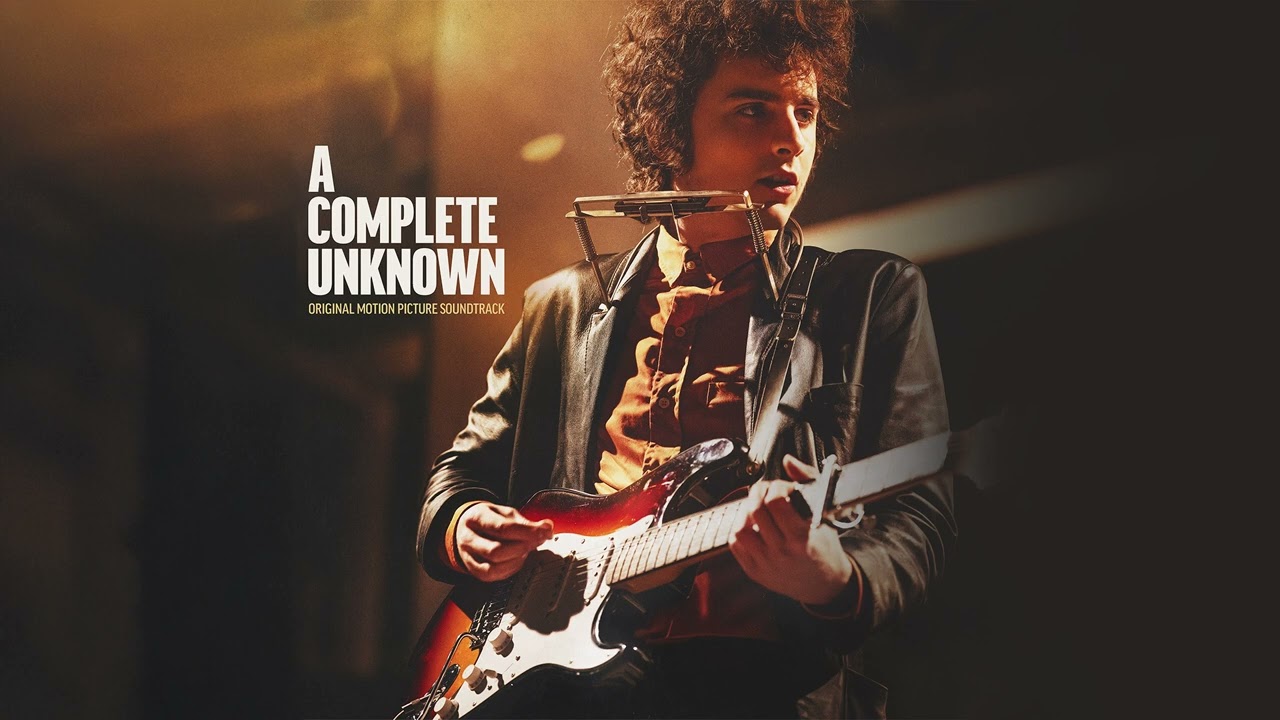

Biopics about musicians have quietly become a trend over the past few years. There’s been films about Queen, Elton John, Elvis Presley, Whitney Houston, Amy Winehouse—and that’s just the big ones. The latest addition to this lineup is the Bob Dylan biopic “A Complete Unknown.” Based on Elijah Wald’s 2015 book “Dylan Goes Electric!,” the film uses just two title cards to anchor the years it spans: from Dylan’s arrival in New York in 1961 to the fiasco at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965. As a folk musician, Bob Dylan emerged in the early 1960s as a symbol of social movements, but soon sparked controversy by upending his image—both in terms of his music and his message—and embracing electric guitar and a backing band.

The story of Dylan’s personal journey during this era remains one of the greatest legends in modern pop culture, so it wasn’t strictly necessary to base the movie on one specific book. And “legend” here isn’t meant to turn his significance or fame into hyperbole. A legend isn’t a collection of historical facts—it’s a mixture of uncertain memories, conflicting accounts, ambiguity, and symbolism that loops back to create new stories in the present day. And therein lies the reason this part of Dylan’s life has inspired so many creative works. It’s impossible for “A Complete Unknown” to simply be the cut-and-dried story of a previously unknown musician unleashing his genius on the world, overcoming adversity to achieve great heights of success.

When filmmaker Todd Haynes went after Dylan’s permission to make the 2007 film “I’m Not There,” he was advised by the singer’s manager to avoid using terms like “voice of a generation” or “genius of our time.” Perhaps because of this, “I’m Not There” became a film about Bob Dylan without Bob Dylan, exploring his multifaceted nature through six actors using seven different names. The result? A film that could be subtitled, in Haynes’ own words, “Suppositions on a Film Concerning Dylan.”

Whereas Haynes’ biopic was devoid of Dylan, James Mangold, the director of “A Complete Unknown,” sees the musician as unknowable and elusive. After a young Dylan was heralded as the symbol of a new generation, he decided to break free of what he felt was a contradiction that had been forced upon him. People cheered Dylan on when they heard him sing a whole new kind of song—one that addressed their parents’ generation: “And don’t criticize / What you can’t understand … Your old road is rapidly agin’ … For the times they are a-changin’” (“The Times They Are A-Changin’”). He had achieved what Pete Seeger (Edward Norton in the film) had dreamed so long of. But when people eventually stood in the way of Dylan’s new road, he distanced himself from them, singing “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” with the acoustic guitar sound they wanted to hear from him—a guitar lent to him by Johnny Cash, himself a rebel who sympathized with Dylan. The majority of people, however, failed to understand him, and dismissed him as a traitor. The film takes some creative license and moves an infamous incident from a 1966 Manchester concert, where an audience member calls Dylan “Judas,” back a bit to 1965 (in the same way that Cash is in the audience in the film version, which didn’t really happen). The legend Mangold ultimately wants to retell seems to be the Newport Folk Festival of 1965, and his thesis one that revolves around the curse of fame and Dylan’s ruthless breakthrough.

This might not exactly be groundbreaking, but what makes “A Complete Unknown” unique is the approach it takes to portraying the four years that lead to the climactic 1965 performance. Unlike today, where an artist’s every move is chronicled on social media and YouTube, there’s no great repository of directly verifiable records from Dylan’s early career, although there is, of course, some interaction and influence between creative works—the way Dylan and Bob Neuwirth act like arrogant rock stars later in the movie, for example, can’t help but draw comparisons to the 1967 documentary “Dont Look Back.” Meanwhile, time itself plays an important role in “A Complete Unknown.” In May 1965, Dylan embarked on a tour of the UK. Just two months later, at the Newport Folk Festival in July, he performed “Like a Rolling Stone,” which he had just written and recorded that June. By doing so, and by showing Dylan purchase an electric guitar while in the UK, the film suggests that his tour planted the seeds for his musical transformation.

“Dont Look Back” is the prototype for most music documentaries, backstage films, and even vlogs you’re likely familiar with. Advancements in recording technology and miniaturization at the time allowed filmmakers to capture moments in cars, hotel rooms, and offices, and even follow people as they run through the halls backstage and jump into cars without disturbing their subjects. Consequently, the documentary captured confrontational interviews between Dylan and journalists, noise complaints from hotel staff leading to arguments, and private performances with artists like Joan Baez or Donovan. Extremely intimate footage like this peeled away the mystery of celebrity, exposing the clash between public persona and personal desire. During this period, Dylan appears increasingly disinterested in his early folk sound, openly flying in the face of convention with resolute defiance, and even distancing himself from Baez. As such, “A Complete Unknown” draws from what’s seen in “Dont Look Back” and leaves Dylan’s shifting attitude as chaos shrouded in mystery.

Perhaps the new biopic’s most direct inspiration is the 1967 documentary “Festival” directed by Murray Lerner. The documentary covers the Newport Folk Festival from 1963 to 1966—Dylan played the event from 1963 to 1965. At the time, the director may not have realized what he was committing to the permanent record. In 2007, Lerner re-edited his footage to focus on Dylan’s performances—solo and with other prominent artists—in a new documentary titled “The Other Side of the Mirror.” The film has since become evidence of the backlash and boos hurled from the crowd during Dylan’s 1965 show. It also serves as a vivid record of the festival atmosphere from which “A Complete Unknown” was able to draw from years later.

These two documentaries now stand as a good starting point for modern audiences who might be puzzled by the intense backlash Dylan faced back then. By March 1965, Dylan had already released the album “Bringing It All Back Home,” one half of which was all electric. Then he released “Like a Rolling Stone” as a single a week before the Newport Folk Festival. Dylan’s transformation wasn’t a secret, so why did people react the way they did?

We can start with the obvious. The Newport Folk Festival was part of the counterculture movement, with folk music at its heart. Both the festival organizers and the audience were well aware of Dylan’s new sound ahead of time, but they still saw Dylan as one of them. His set went beyond merely musical innovation—it was a response to their views and a declaration that he pointedly disagreed. For example, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, as mentioned briefly in the film, performed an electric set, too, but it caused no controversy. Of course, questions still remain about what really happened. For one thing, unlike in the movie version, he wasn’t the closing act, which may have contributed to tensions. It’s also true that there were boos from the audience, but the harshest judgment came after Dylan played only three songs before leaving the stage—something that some say was twisted through Lerner’s editing choices.

The clearest answer comes from someone in “A Complete Unknown.” When Pete Seeger tried to stop the show, he was stopped by Joe Boyd, then the production manager, as he took control of the console and shouted for a need for open ears. “So many big historical events become hinges of history in retrospect,” Boyd recently commented, “but this was one of those events that everybody [was] conscious of as it was happening.” He’s not saying he knew what the future would hold, but that, in that moment, an entire generation of young people empathized with and supported this musician pursuing his artistic vision without worrying about his popularity or image. Is it really that surprising that the revolution in pop music that took place in the late 1960s began with a mixture of boos and cheers? Plenty of people in the audience at the climax of the film look happy—so it would seem the ending isn’t really about the boos at all.