“I got into K-dramas around 2005 with classic rom-com dramas like My Girl and My Lovely Sam Soon as my mom and I would bond over watching these dramas together. My family also watched Korean variety shows such as Family Outing and Running Man together regularly. I was one of the second-generation fans that got into K-pop during the era of Super Junior, SHINee, Girls’ Generation, the Wonder Girls etc. as it was all the rage in middle school. My friend and I were avid fans of K-pop at the time and since I was pretty up to date with what was happening in the K-pop scene at the time, I first heard of BTS when the news came out that there was a new boy group debuting. We listened to “No More Dream” and “We Are Bulletproof Pt. 2” constantly when it came out, and I was particularly drawn to the lyrics and hip hop genre of the two songs as they were very different from what the rest of K-pop was talking about at the time.”

If you went to school in Korea in the 2010s, this will sound like a familiar tale. For some people, it might sound exactly like their own experiences. But the above is Faith’s story, a BTS fan who was born and went to school in Singapore and is now a translator with a well-known fan translation account. She says that “K-pop has been very big in Singapore for quite a long time now.” It was commonplace for even minor fans in countries neighboring hers to listen to K-pop when they were teenagers as well. Chika, another translator for the fan account who lives in Indonesia, recalls having an experience similar to Faith’s: “When I was in high school, a lot of my friends were K-pop fans, so I was already exposed to K-pop music from 2010.” BEE, a BLACKPINK fan living in the Philippines, runs a Philippines-based news account on social media that provides updates related to the K-pop group. BEE was “one of those kids who danced to these popular songs” and gave examples of hits by 4minute, 2NE1, Wonder Girls and Girls’ Generation.

-

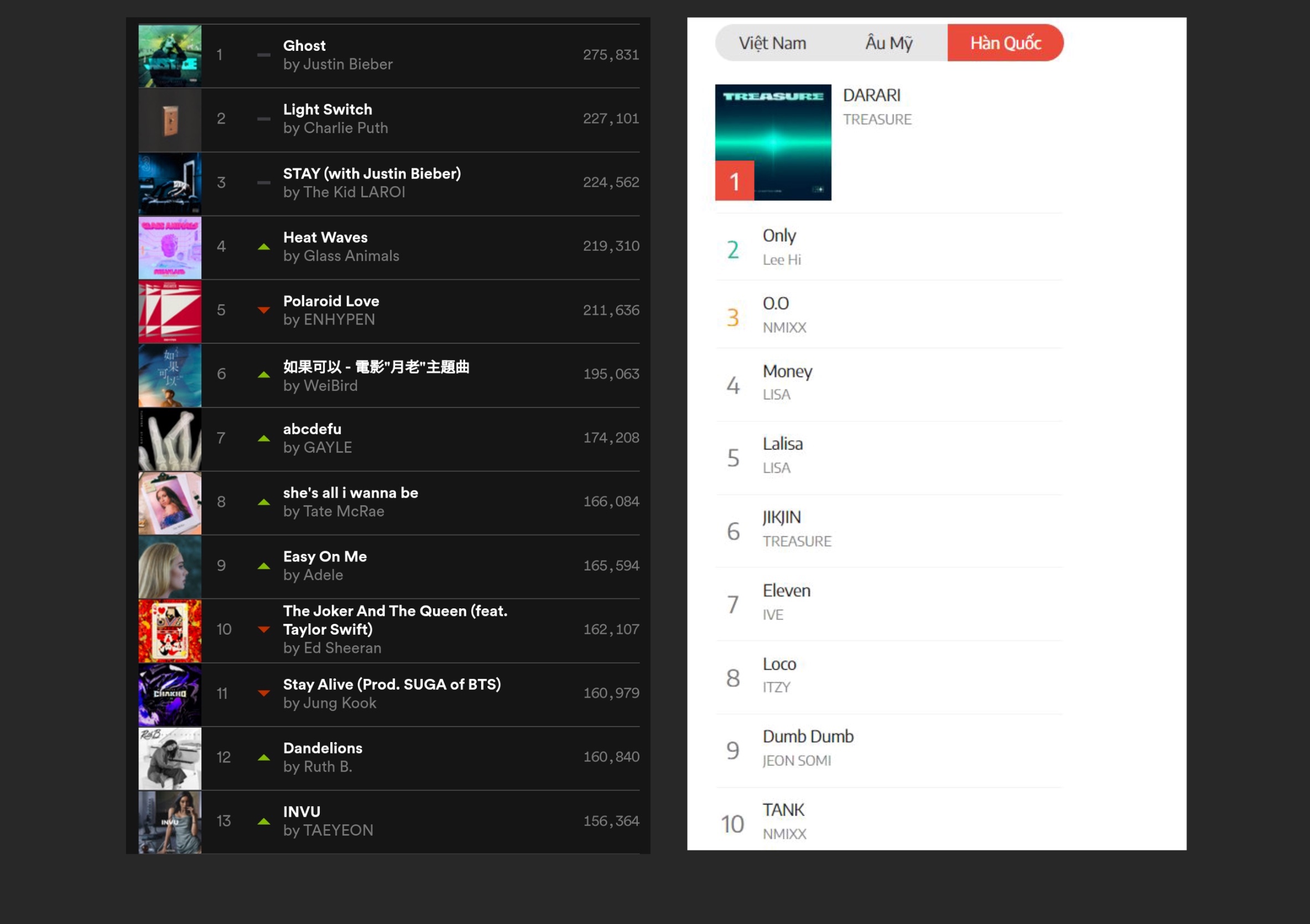

©️ SPOTIFY CHARTS WEEKLY TOP 200 SINGAPORE (2022/02/24) NHACCUATUI.COM (2022/03/15)

©️ SPOTIFY CHARTS WEEKLY TOP 200 SINGAPORE (2022/02/24) NHACCUATUI.COM (2022/03/15)

As Faith’s, Chika’s and BEE’s stories make clear, Korean pop culture has long been easily accessible in Southeast Asia, and was introduced under the label “Hallyu,” or Korean wave. And now, after over a decade, it is becoming more popular still, in a way that’s even closer to fans’ hearts. Currently (as of February 24), Jung Kook’s “Stay Alive” (prod. SUGA of BTS), as well as new songs by ENHYPEN, TREASURE and TAEYEON are sitting comfortably in the upper ranks of the weekly Spotify charts in Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. On their website’s front page, NhacCuaTui, the dominant streaming service in Vietnam, separates its chart listings into Vietnamese, UK/US and Korean pop, and eight of the top 10 most-watched music videos in Singapore for 2020 were from K-pop artists, including BLACKPINK and BTS. Shin Jin-se, a correspondent for the Korean Foundation for International Cultural Exchange (KOFICE), has lived in Indonesia for 14 years and said that “K-pop songs account for 30 to 40% of the top 100 songs on JOOX, the streaming service with the greatest number of users in the region.” The genre’s popularity on charts spanning numerous Southeast Asian countries reflects how the average person living there feels about music. Cho Nam-seok, a dispatched teacher at the King Sejong Institute who has lived in Thailand for four years while teaching Korean, said people “don’t just play K-pop music at Korean restaurants or Korean supermarkets, where they want to create a Korean atmosphere—you can hear it all the time in the street, in shops, and at the gym.”

“K-pop can be seen as one part of mainstream culture in Malaysia,” Hong Sungah, another correspondent for KOFICE, explained. “Female K-pop artists influence the makeup, contact lenses, glasses, hairstyles and fashion here, and glasses stores advertise that they’re selling Korean-style colored contact lenses and glasses.” BEE’s experiences have been similar: She noted how, “during the [‘How You Like That’] era of BLACKPINK, Jennie’s hairstyle became a trend among the female celebrities and women” in the Philippines. And the popularity of K-pop artists like BLACKPINK doesn’t stop at their appearance. The owner of an Indonesian BLACKPINK fan account said the group’s members “definitely have a good impact on my life. They are highly motivating, and I have learned how to achieve success from them.” BEE has also found direction in her life thanks to BLACKPINK, saying, “I want to be a successful woman too, just like them. They always give me positive energy in many ways, especially when I feel down.” Kim Sejin, a member of KOFICE and associate manager of the K-pop Dance Academy project targeted at students in Buriram Province, Thailand, the hometown of LISA from BLACKPINK, explained how the idol is seen to have a positive influence locally. On Thai PBS, a local state-run broadcaster, Kim said that “LISA is a source of positive energy for Thai students pursuing their dreams.” Meanwhile, Hong said that “BLACKPINK has become hugely popular in Malaysia, and it seems like their effort to make their dreams come true in BLACKPINK THE MOVIE inspired the younger generation in Malaysia.”

And now the K-pop trend has entered a new stage. According to an overseas correspondent report Hong posted to the KOFICE website in 2019 titled “Malaysia’s Changing Fan Club Culture,” the K-pop fandoms get together to hold “birthday cafe” events in Malaysia just as they do in Korea: Fans rent out small cafes on anniversaries of dates such as an artist’s debut or their birthday and hold so-called birthday cafe events where they browse or give away items featuring the artist. The report says that, before the pandemic, around 40 such events were held in cafes around Malaysia every month. Other K-pop fan trends similar to birthday cafes that got their start in Korea are spreading throughout Southeast Asia as well. As K-pop and other Korean pop culture have been spreading over the course of 10 plus years, the groups of fans enjoying it are beginning to grow similar to one another. This has led to times where fans in Malaysia come together in solidarity of some cause based on their mutual love of fan culture. Hong gives a donation drive/volunteer … organized by ARMY, the BTS fandom, as an example case within the Malaysian fan community in another of her reports, “BTS Fans Continue Acts of Kindness with the BTS Meal.” When the BTS Meal from McDonald’s went on sale globally in May 2021, Malaysian ARMY made headlines after making repeated donations of the fast-food meal for medical staff. Just as in Korea, members of the fandom in Malaysia are strengthening ties and the community is dynamic enough to make group donations together.

When it first came to Southeast Asia, K-pop was an outlier. “Indonesia has a mature live band scene, and dangdut, a genre similar to Korean trot music, is popular,” Shin, the other correspondent, said. “It’s fairly different compared to the music coming out of the established Indonesian music industry.” Hong said that, these days, “Malays prefer calm, quiet acoustic ballads, while Chinese Malaysians listen to more Chinese music, usually.” Unexpectedly, however, young people in Southeast Asia became interested in K-pop because they saw it as something new and different. Chika, in Indonesia, recalled being “amazed by the [BTS] song ‘Not Today’ because of the catchy music, inspiring lyrics and beautiful scenic visuals in the music video.” K-pop’s “catchy melodies and the singers’ appearances and dancing” are, as Areerat Luksanawaree, who lives in the Thai province of Chonburi and is studying Korean at the King Sejong Institute, said, the reasons most often cited for the genre’s popularity. JAM, who also helps run the BLACKPINK fan account in the Philippines, said she enjoys watching the music videos “as they really exerted effort with their style, choreography, set and fashion.”

Beyond the process of accepting and embodying an outsider genre over the course of 10 years, there is also background context that is unique to Southeast Asia. In a paper published by Sujeong Kim in 2012, she describes Southeast Asia as being “generally open and having an open attitude toward coexistence on the basis of their ethnic and cultural diversity.”(Kim Sujeong, “The Characteristics of the Korean Wave in Southeast Asia and the Transnational Flow of Cultural Taste.” Broadcasting & Communication, vol. 3, p. 23. 2012) The different countries that make up Southeast Asia have various state religions, including Catholicism, Christianity, Islam and Buddhism. Several religions can also coexist in one country, and there are several examples of linguistic variety as well. As noted by Hong, “Malaysia is grouped into people of Malay, Chinese and Indian descent, and major belief systems—from Islam, practiced by most Malays, to Buddhism, Taoism and Hinduism—coexist with folk religions.” In Singapore, there are a total of four official languages in use, with channels available in each language. Although Southeast Asia is home to a diverse group of countries, they share some religions in common, meaning they are used to intimate cultural exchanges through political and economic cooperation. “Indonesia, along with Malaysia, Brunei, southern Thailand and the island Mindanao in the Philippines, are considered to be a part of the Muslim world,” Shin explained, “and there exists an emotional and cultural closeness between” the different countries. Moreover, Southeast Asia has experience with importing media from various countries as rapid development in the area led to an explosion in interest toward pop culture, according to Kim’s paper. As a result, the region began to develop a rich context of many layers thanks to remaining relatively open to new cultures and the potential for popular culture from one region to cross over into another became very high. It seems Korean dramas and K-pop entered the area through similar means and as another culture destined to become yet another layer.

And herein lies the reason the K-pop industry should be paying attention to Southeast Asia at this moment in time. As history shows, with its relatively open stance on other cultures and their unique identities, the region has the impetus to progress toward a new culture of their own as it quickly and easily embraces others. ACE, also a contributor to the Filipino BLACKPINK fan account, said she believes P-pop (Pinoy pop) also shows “the influence of K-pop” in “the fashion sense and the style of music videos.” BEE, too, noted the parallels to K-pop; in particular, how a P-pop artist will “undergo training too, just like K-pop artists.” The K-pop influence is evident when seeing the music videos that pop up after searching for P-pop groups, with their combination of K-pop’s characteristic member roles, dances and music incorporating rap and vocals. But these Southeast Asian groups aren’t limited by their K-pop influences. Hong describes how four-member Malaysian girl group DOLLA, who debuted in 2020, “received a lot of attention for being pop stars armed with fashion and music unheard of in Malaysia.” The members of the group even have “specific roles in singing, rapping and dancing” that are “characteristic of similar groups debuting from the K-pop system,” Melissa, a team coordinator for the BTS fan translation account mentioned earlier who’s living in Malaysia, pointed out. Yet “they still maintain a Malaysian identity, such as mixing the Malay and English languages in their songs.” In Thailand, T-pop groups such as 4EVE and ATLAS promote their music using the same kind of marketing strategies employed in K-pop, uploading vlogs, behind-the-scenes videos, special stripped-down performances and pre-debut footage showing each member to their YouTube channels alongside the expected music videos. When one country or culture is influenced by another, it doesn’t stop at borrowing from it—just as they did with K-pop, embracing other cultures leads to the start of a whole new culture. New pop stars are being born in Southeast Asia and laying the groundwork for how to promote their music to people in more countries by using K-pop production methods and marketing tools but with their own cultural foundation.

If you were to look at several K-pop artists’ YouTube channels and sort their subscribers by country, you would probably find at least one Southeast Asian country in the top five each time. The same is true of Twitter, which has become an open forum for different fandoms, allowing them to share information related to K-pop stars and K-pop in general. Looking at a 2020 article released in a collaboration between Twitter Korea and Space Oddity’s K-Pop Radar titled “Celebrating 10 years of #KpopTwitter,” six of the top 20 countries for K-pop-related conversations by volume—Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia, ranking first, third, fourth and seventh, respectively—were in Southeast Asia. Four Southeast Asian countries were in the top 10 for number of users tweeting about K-pop, showing both high interest and high activity. And that’s not all: The market in Southeast Asia is expected to see even more growth in the future. The average annual growth rate of the content market in six of the member states of the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), an area with a population of roughly 660 million people, is 3.87%, outpacing the estimated global figure of 2.83%. It also accounts for 14.1% of Korea’s content export market as of 2019, making it the largest region after Greater China and Japan. There’s already a sizable fan base and the proportion of “passionate consumers” of Korean content overall is relatively high. At the same time, the process through which Southeast Asia has come to embrace K-pop and its fandom culture can be understood to be a result of the increasing influence the region has on the K-pop industry as well.

DITA, who debuted with the K-pop group SECRET NUMBER in 2020, is from Indonesia, and Hanbin, from Vietnam, is a member of TEMPEST, having debuted just this month. This shouldn’t be seen as a strategy to target specific markets; it’s only natural that K-pop artists will continue to arise from countries where the style and culture of K-pop have been popular for over a decade. At its core, K-pop is a complex combination of genres, styles and marketing techniques that has gradually changed to keep up with the times by incorporating various styles of music and sentiments found in Korea and abroad as well. And now it’s Southeast Asia’s turn to make its mark on the K-pop scene. The region is becoming one of the pillars of K-pop, gradually changing the foundations of the genre without Koreans ever noticing.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.

- Fans, Their Voyage in the room2021.03.16

- Hangeul holds the ARMY world together2021.10.09

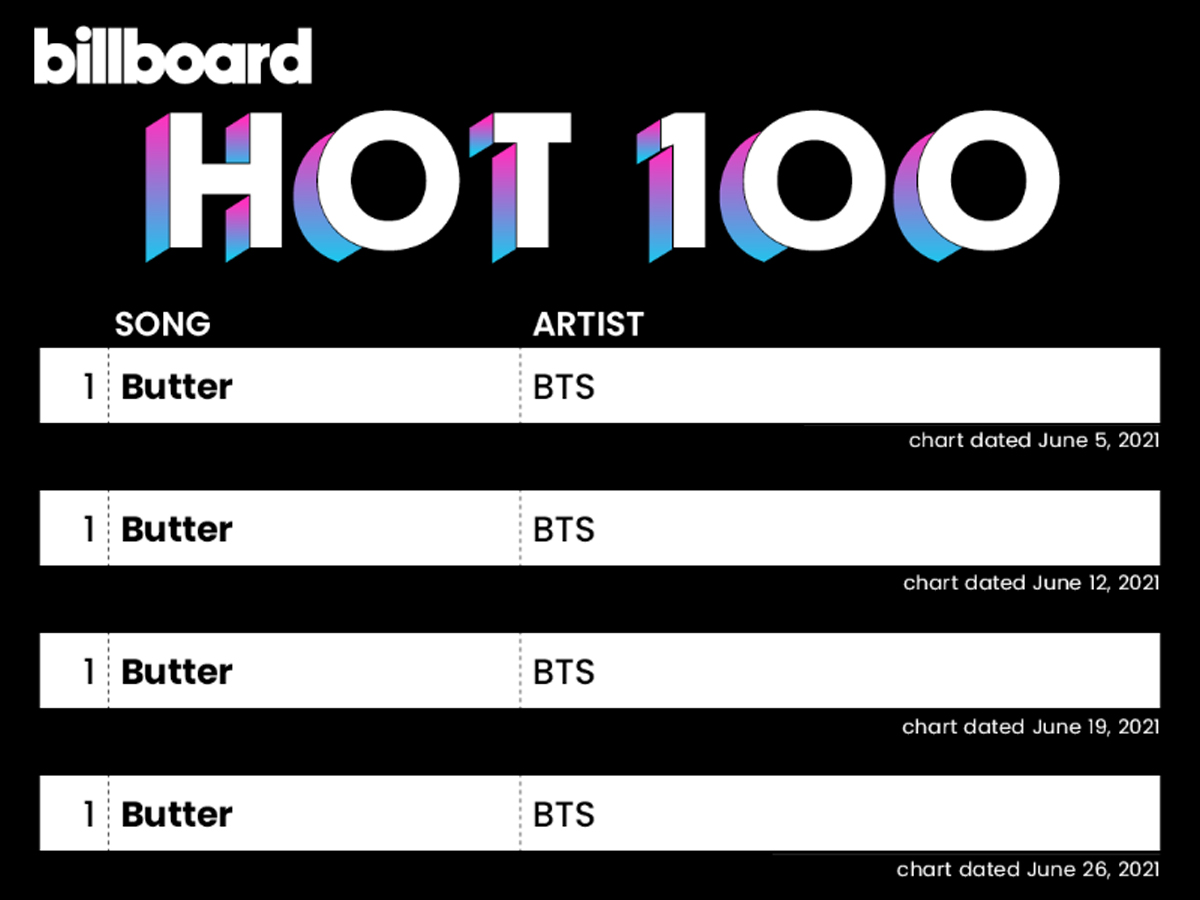

- What BTS achieved in the US2021.07.12