NoW

[NoW] Picasso’s Eternal Passion

Pablo Picasso Retrospective

2021.06.04

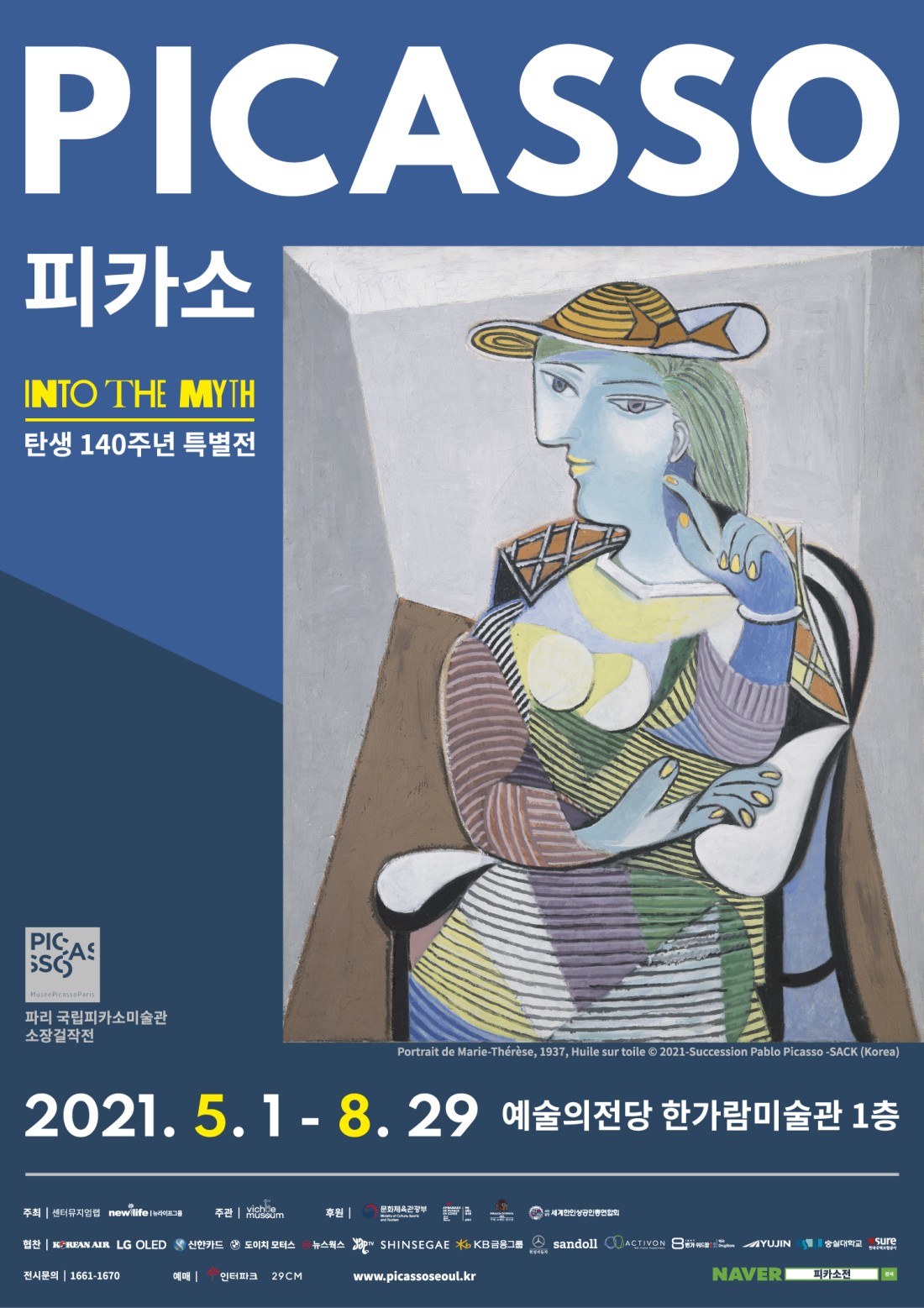

The Picasso painting Massacre in Korea, which depicts the outbreak of the Korean War on June 25, 1950, was unveiled in Korea for the first time at the Hangaram Art Museum. The retrospective features various collected works on loan from the Musée Picasso in Paris, France, like paintings, sculptures, ceramics and more. The collection of two-dimensional and three-dimensional works offer a new visual experience to people who have up to this point only been familiar with his cubist paintings and gives them a chance to experience new ways of thinking and inspiration.

The swath of works cover the seven themes that span from Picasso’s early to later works and show such diverse, unique creativity that it’s difficult to imagine one artist was responsible for all of them. Massacre in Korea, the main work being promoted, is hanging in the sixth section, called War and Peace Around Massacre in Korea. Picasso was a member of the French Communist Party when he painted the piece on commission, and as Korea was in an era of conflicting ideologies the painting was on the list of artworks prohibited from entry into the country until the 1980s. Given that the artist had never visited Korea and crafted his piece based solely on things he had heard, it’s impossible to separate the work from the aims and views of the era. However, because it’s difficult to analyze the nation or political sides in the painting, and because the focus falls on the fear and grief of the people staring down the army’s weapons, it’s highly valuable as an antiwar piece that shows how Picasso denounced the horrors of war and longed for peace. Seeing the way he places emphasis on the use of color in this piece gives us a chance to compare it to Picasso’s earlier antiwar pieces, Guernica and The Charnel House, and reflect on how his artistic endeavors changed over time.

Such efforts led Picasso through styles like the young artist’s early work, the spotlight on gloomy hues in his Blue Period, and the more dazzling, lively Rose Period, which gave way to Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, regarded as a forerunner to cubism. Though it was a monumental cubist work considered to have freed views from classical perceptions, it didn’t receive universal praise from the outset; innovation is, inevitably, met with unfamiliarity and shock. That didn’t stop Picasso from experimenting not only with variations on cubism but also other new approaches to his work like neoclassicism and surrealism without hesitation. His passion wasn’t confined to painting, either: He worked in such multidisciplinary artistic modes as sculpting, ceramics, poetry and theater throughout his life. As such, Picasso’s name has become synonymous with artists today. But Picasso was interested in more than just trying new things. He is quoted as having said, “All I ever did in life was love. I can’t begin to think of a life without love.” Love, and the women he loved, occupied a major part of Picasso’s working world. He faced a number of scandals and criticism as a result, but approached his work as something to be drawn from the mind, not from what is seen, so meeting new people would naturally have led him to trying new things.

To this day, Picasso is considered the 20th century’s greatest artist, having left behind artwork beloved by so many. It’s not hard to imagine just how unconventional Picasso’s passion and endless attempts at freedom of expression were for his time in the passage of art history given his new stylistic changes were so remarkably distinct from that of the previous era. The reason such artistic adventurousness can provoke appreciation in us even today is the value of the experimentation and the energy of the creation still living within the works. And that’s why Picasso will be remembered as the eternal master and pioneer of 20th-century art.

The swath of works cover the seven themes that span from Picasso’s early to later works and show such diverse, unique creativity that it’s difficult to imagine one artist was responsible for all of them. Massacre in Korea, the main work being promoted, is hanging in the sixth section, called War and Peace Around Massacre in Korea. Picasso was a member of the French Communist Party when he painted the piece on commission, and as Korea was in an era of conflicting ideologies the painting was on the list of artworks prohibited from entry into the country until the 1980s. Given that the artist had never visited Korea and crafted his piece based solely on things he had heard, it’s impossible to separate the work from the aims and views of the era. However, because it’s difficult to analyze the nation or political sides in the painting, and because the focus falls on the fear and grief of the people staring down the army’s weapons, it’s highly valuable as an antiwar piece that shows how Picasso denounced the horrors of war and longed for peace. Seeing the way he places emphasis on the use of color in this piece gives us a chance to compare it to Picasso’s earlier antiwar pieces, Guernica and The Charnel House, and reflect on how his artistic endeavors changed over time.

Such efforts led Picasso through styles like the young artist’s early work, the spotlight on gloomy hues in his Blue Period, and the more dazzling, lively Rose Period, which gave way to Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, regarded as a forerunner to cubism. Though it was a monumental cubist work considered to have freed views from classical perceptions, it didn’t receive universal praise from the outset; innovation is, inevitably, met with unfamiliarity and shock. That didn’t stop Picasso from experimenting not only with variations on cubism but also other new approaches to his work like neoclassicism and surrealism without hesitation. His passion wasn’t confined to painting, either: He worked in such multidisciplinary artistic modes as sculpting, ceramics, poetry and theater throughout his life. As such, Picasso’s name has become synonymous with artists today. But Picasso was interested in more than just trying new things. He is quoted as having said, “All I ever did in life was love. I can’t begin to think of a life without love.” Love, and the women he loved, occupied a major part of Picasso’s working world. He faced a number of scandals and criticism as a result, but approached his work as something to be drawn from the mind, not from what is seen, so meeting new people would naturally have led him to trying new things.

To this day, Picasso is considered the 20th century’s greatest artist, having left behind artwork beloved by so many. It’s not hard to imagine just how unconventional Picasso’s passion and endless attempts at freedom of expression were for his time in the passage of art history given his new stylistic changes were so remarkably distinct from that of the previous era. The reason such artistic adventurousness can provoke appreciation in us even today is the value of the experimentation and the energy of the creation still living within the works. And that’s why Picasso will be remembered as the eternal master and pioneer of 20th-century art.

-

© vichae artmuseum

© vichae artmuseum

TRIVIA

Cubism

An early 20th-century art movement based in Paris, France. The term was coined in 1908 when Matisse commented that Braque’s work looked like “cubic oddities,” and is regarded as the revolution that liberated artists from the traditions that had governed fine art since the Renaissance. The subject on the canvas is organized into geometric shapes, and the spatiality and viewpoints are expressed through multiple perspectives. Cubism is further divided into three periods: early cubism, analytic cubism and synthetic cubism.

Cubism

An early 20th-century art movement based in Paris, France. The term was coined in 1908 when Matisse commented that Braque’s work looked like “cubic oddities,” and is regarded as the revolution that liberated artists from the traditions that had governed fine art since the Renaissance. The subject on the canvas is organized into geometric shapes, and the spatiality and viewpoints are expressed through multiple perspectives. Cubism is further divided into three periods: early cubism, analytic cubism and synthetic cubism.

Article. Jangro Lee (Art Critic)

Design. Yurim Jeon

Copyright © Weverse Magazine. All rights reserved.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.

Read More

- [NoW] A party for Andy Warhol2021.04.09

- [NoW] Lee Bul : Beginning2021.05.07