On March 16 in the US, a white man entered three Asian-run spas in Atlanta, Georgia and opened fire. He killed eight people. Among the victims were six Asian women, four of whom were Korean. It’s been one month since the congresswoman Representative Judy Chu revealed that over 100 hate crimes against Asians are reported in the US every day, and about a year since last March when the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

The incident was particularly shocking to citizens, even in the midst of still higher rates of hate crimes against Asians in the US in 2021, due not only to the shooter’s distorted views on race and gender, but also the attitude of the local police. The police were quoted through a spokesperson as having said the offender “had a bad day” and failed to charge him with a hate crime despite having specifically targeted Asian women; hate crimes carry a greater sentence. It took more than two months for the prosecutors to deem the incident a hate crime, and on May 11, the Atlanta shooting became the first case to be applied with the hate crime law since it took effect in Georgia.

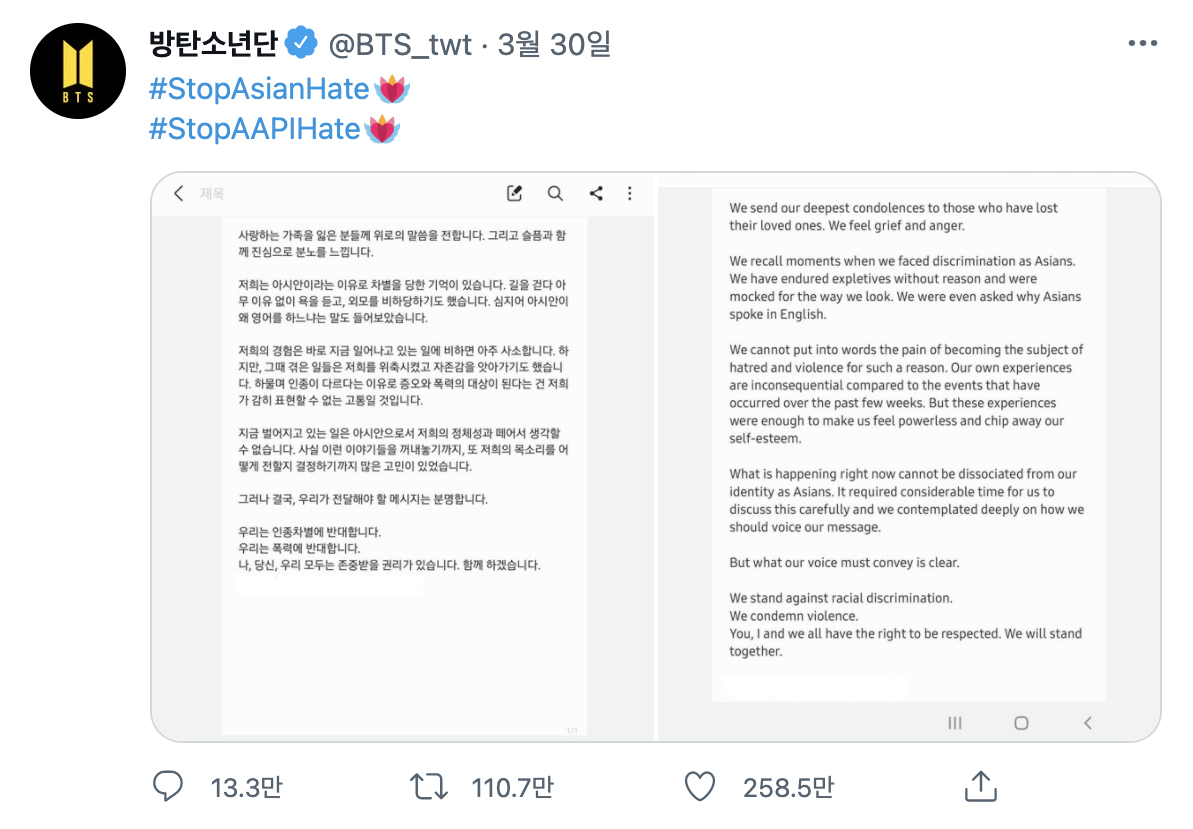

The opinions and resistance of many citizens was the driving force behind this decision. A lot of people spoke out about this horrible crime and how poorly the response was handled. Asian celebrities were especially assertive as they used their platforms to express their views. Korean Canadian-American actor Sandra Oh spoke out at an outdoor rally in Pittsburgh, while singer and Atlanta native Eric Nam wrote an opinion piece for Time magazine taking a firm stance against threats to Asians’ human rights, a sentiment he repeated in an interview with CNN. Across social media, the hashtags #StopAsianHate and #StopAAPIHate—using a term referring to Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders—spread with messages of condemnation, calling for respect for Asians. On March 29, BTS posted a statement which included the hashtag to their Twitter account as well. The short letter expressed condolences to the bereaved families of the victims of the Atlanta massacre, touched on discrimination they have faced themselves, and reaffirmed their sense of Asian identity. The post spread exponentially across the globe as it was rapidly retweeted.

Let’s turn back the clock a bit. On February 25, a host on German broadcaster BR’s Bayern 3 radio station in Bavaria spat out racist remarks about BTS. From offensive words, to comparisons to the coronavirus, to suggesting the group will have to take a “vacation” to North Korea—a term used by the Nazis to trick Jews when they forced them into concentration camps—it was a textbook case of hatred toward Asians. Members of BTS’s fanbase, ARMY, in Germany and throughout the world flooded the radio station with demands for an immediately apology. The station issued an apology soon after, but it only fanned the flames further, saying it “is his personal opinion,” and that if fans “found his statements hurtful or racist … we deeply apologize.” ARMY pressured the broadcaster persistently to issue a proper apology; the station issued a second, revised statement the following day.

It wasn’t the first time BTS had been the target of such racist remarks in Western media. When the group first gained international recognition after winning the Billboard Music Award for Top Social Artist in 2017, most mainstream press dismissed them as Internet-famous foreign singers or a passing fad. But their popularity soared and just one year after the incident the group filled Citi Field stadium in New York City. By 2019, they were big enough to tour the world, stadium after stadium. Only once BTS had reached a level where they became impossible to ignore did the mainstream media begin to belatedly acknowledge and pay attention to them. Some welcomed the arrival of these new stars with an open mind, but there were also those who stubbornly saw BTS as outsiders because they are not white and are from Korea. As BTS’s influence grew, those people viewed the group with suspicion as outsiders who threatened the established industry and tried to cut the group down from time to time. It was that same year, in 2019, when the tendency for racist remarks big and small toward BTS really started to pile up. In addition to the explicitly racist remarks already mentioned, there were countless cases of microaggressions including insincere articles and subtly negative comments. Even celebrities as successful as themselves have been othered and discriminated against for being non-white and Asian.

There’s a long history of hatred from Westerners toward Asians and its forms are as varied as the Asian continent is vast. To narrow things down to prejudice against Northeast Asians in American society, Yellow Peril is a prime example. Yellow Peril is the vague fear that Northeast Asians will threaten and overthrow Western civilization. It was used as a recurring piece of political propaganda.

It all started in the 19th century. During the California Gold Rush, many Chinese immigrants settled in the Western United States. In the latter half of the century, hatred began to escalate over the idea that Chinese immigrants stole jobs from white people in the region. The Yellow Peril was a good excuse to vent resentment during an unstable and dreary recession using the underprivileged as a scapegoat. The prevailing atmosphere of hatred and discrimination surfaced in the form of frequent lynchings and murders, which came to a head in the LA Chinese massacre of 1871. Yet 19th-century America did not put the brakes on this social unrest. Moreover, in 1882, US Congress enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first act of its kind to obstruct the immigration of a specific nationality. This was followed in 1924 by a revision to the immigration laws that imposed a quota on immigrants by national origin. This was a de facto “Asian Exclusion Act,” one that allocated the total number of immigrants allowed per year by country to accommodate Europeans while suppressing the Asian community, and one example of the hatred that stems from society that then infiltrates the national system.

Mid-20th-century history also shows Japanese immigrants being indiscriminately interned during World War II because their home country was an enemy during the war. The reason Japanese immigrants were wronged against so vehemently compared to Germans and Italians, despite also being from enemy countries, largely came down to racial profiling, or discriminating or targeting someone based on their ethnicity. The Yellow Peril scare was said to have been reignited in the late 20th century as American industry was losing ground to competition with Japanese companies, but faded over time. Yet as we entered the 21st century, the fear along with discrimination against other ethnicities has been brazenly revived as China became an increasing economic threat. And now such feelings of hatred have amounted to committing violent crimes against Asians.

Although Koreans suffered their own specific hardship under the hand of the Japanese Empire during colonial rule, they have also suffered hatred as part of a larger group based solely on their skin color. After all, those who would knowingly hate others also make crude generalizations: Whether Chinese, Japanese or Korean, non-white Asians were discriminated against, and it’s the same now as it was then. For Koreans, historical background such as the Korean War added to the prejudice against them, with common examples including othering, “yellow fever” especially associated with Asian women and other related fetishes, and the myth of the model minority. It’s not only Northeast Asians but also people from Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent and Southwest Asia as well as Pacific Islanders who are suffering from similar problems and their own unique situations. I regret that I can’t cover each one as it deserves in such a short article.

Some of the discrimination taking place against Asians in 2021 can be said to be a part of the Yellow Peril mindset. There’s no reason for international trade conflicts or infectious diseases such as COVID-19 to lead to racial discrimination. And yet, hate crimes against Asians, particularly women and the elderly, have started to spread like wildfire in large cities in particular.. It has become noticeably more common to hear abusive language or be assaulted in the street--just for being Asian. As the situation exacerbated, Asian Americans who could no longer stand by as they witnessed the pain of their people have begun to band together. It was from this background that the #StopAAPIHate movement was born.

-

© shutterstock

© shutterstock

The Bayern 3 discrimination incident in February wasn’t much different in intensity or means from what BTS had already experienced, but the responses were different that in previous years. Different from when it was only BTS’s fanbase ARMY asking for an apology, this time famous American singers and songwriters, including BTS collaborators Halsey and Steve Aoki, came forward to criticize the host’s racism. Columbia Records, Sony Music, Grammys host the Recording Academy, and other major players in the music industry also issued statements in support of the cause (though without mentioning BTS) using the #StopAAPIHate hashtag. It may be due to BTS’s rise in status, and the impact of the 2020 #BlackLivesMatter demonstrations and the #StopAAPIHate movement that started last year in America that led them to begin to rethink racial minority rights awareness, that had the greatest effect. Above all else, artists who had come to know each other through working together showed their solidarity, proving BTS had not only succeeded commercially but had also come to steadily call for solidarity while fostering reciprocal personal relationships in unfamiliar territory. Media outlets such as Billboard who had at first been half-hearted in addressing the situation, now published articles.

And then, April 10. Chilean TV network Mega aired a racist comedy sketch about BTS. Starting in Chile, ARMY around the world denounced the network on social media and demanded an apology. It might be tiring to deal with such offensive content over and over again, but the response of ARMY was unwavering. What’s interesting is that major news outlets, including The New York Times, released articles the moment the incident became a major issue in the United States on the 12th. With influential media around the world paying attention, the TV network quickly issued an apology.

Racism like this continues to be directed toward BTS and toward Asians as a whole, but the way the world around them responds is changing over time. Notably, the racist Chilean TV incident was the first such incident to involve BTS since the band released their #StopAAPIHate statement. Even before this, BTS were famous figures, and so it would have made sense had the discrimination they suffered been covered. Nevertheless, Western media were reluctant to report about it aggressively. Korean media wasn’t very interested, either. The way Western media avoided commenting on the controversy was typical of model minority discrimination; there is a misunderstanding that, because many Northeast Asian and Indian people have high educational aspirations and have attained success or relative social status, they aren’t subjected to discrimination or hatred. Asians suffer from this kind of microaggression, which invalidates their experience of being discriminated against, quite frequently. However, after releasing their statement, BTS became more than just Asian celebrities; they were party to recognizing Asian identity and vocal participants in the #StopAAPIHate movement. The media’s quick action is their way to shed light on BTS, who have become key figures in the fight for important social issues.

It’s difficult to conclude that progress regarding Asian rights awareness in the US and in the West has been made just because of a more expedient reaction to discrimination against BTS. However, I would like to point out that this quicker response didn’t come from nowhere; the change is the result of a combined effort: ARMY’s persistence in fighting social issues and consistently raising questions, and the decision made by BTS and their fellow performers to not be silent. It’s a small step, but I choose to see it as progress compared to the place where we started.

The Anti-Asian Hate Crimes, more commonly known as the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act was passed in the United States last month. President Joe Biden signed the bill into law adding that, “Silence is complicity.” However hate crimes against Asian people are still ongoing nonetheless. Another Asian woman was assaulted in the streets in the outskirts of LA just a few days before writing this article, on June 14 which shows that crimes do not stop immediately after the Act is passed. Despite all the progress of late, it’s being met with strong backlash at the same time. It can be frustrating, but there’s no way to face it but head on.

The cover of the April 5 issue of the American weekly magazine The New Yorker made headlines. In the illustration, an Asian mother and her daughter are standing on a subway platform. The two are looking around, tightly holding hands, and the mother is looking at the watch on her wrist. They appear to be waiting for the train, which is running late. What makes the picture so impressive is the way it depicts how Asians, as minorities, are at risk of suffering a hate crime even while in an everyday location like a subway station but, at the same time, doesn’t paint them as being fragile. R. Kikuo Johnson, the artist behind the cover, explained in an interview with The Hankyoreh that he wanted them “to be very alert and anxious without appearing overtly fearful.” The illustration is titled Delayed, and appears to be derived from the maxim, “justice delayed is justice denied.”

Justice in the form of respect for human rights and equality for Asians must be achieved. Society is slow to change, but there are many people who haven’t given up and are raising their voices and demanding immediate justice. As a face of Asian lives, BTS, naturally, may play a role here as well, however big or small. In their statement, they concluded by saying that they would oppose racism and violence “together.” The power to endure an arduous battle is found in solidarity. I hope the world I wish to see comes sooner than later.

May the victims who lost their lives in the Atlanta shooting and other hate crimes against Asians rest in peace.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.