“I felt like the distance between BTS and me has narrowed,” said YouTuber hamonthly, explaining what the use of International Sign (IS) in the choreography for BTS’s “Permission to Dance” means to her. hamonthly, who identifies as deaf and uploads content to her eponymous YouTube channel related to her life and hearing loss, posted a reaction video to “Permission to Dance” in July, the reason being that the choreography for the music video, as is widely known, features three signs from IS: those for fun, dance and peace. According to Son Sung Deuk, leader of the BIGHIT MUSIC performance directing team, the IS featured in the choreography was “planned with the intention to have a performance that everyone can follow without difficulty—the result of expanding the scope of ‘everyone’ to be as wide as possible.”

“From the standpoint of a sign language user, sign language is their first language,” hamonthly said, explaining how IS made narrowing that gap possible. For sign language users, she said, “Korean is essentially a foreign language,” so it’s similar to the way we welcome meeting a user of the same language in a different country. As hamonthly said, for deaf people, sign language is their first language. According to the Korean Sign Language Act, passed in 2016, KSL is an official language with equal standing to Korean. The two languages have their own unique grammar systems and use different word orders. IS, meanwhile, presents a means for deaf people who use sign languages from different countries to communicate with one another and, because there’s no firmly established system like there is with KSL or American Sign Language, it’s subject to change depending on the region and its users; as such, its exact definition remains up for debate. This meant that “there were difficulties because International Sign isn’t officially regulated,” Son explained, adding that they “ran reviews focusing on whether the meaning was being accurately conveyed to deaf individuals.”

Everyone thinks and establishes their identity through language. Unlike people who can hear, deaf people must “see” their language, and therefore sign language is a part of who they are. According to Jung Heechan, executive director of the Korea Association of the Deaf, “International Sign is created through signs that have a compatible meaning with each other.” He called the communication that its users generate between themselves the core of IS, adding, “Deaf culture possesses its own unique identity and thoughts.” hamonthly feels likewise: “Korean Sign Language gave me an answer to the question, ‘Who am I?’ ” She pointed out how it’s a positive development that sign language was incorporated into the “da na na na” part of “Permission to Dance” since KSL is its own language and not a substitute for Korean. It was something she could enjoy that wasn’t directly bound to the music because “sounds and beats are important in music, but they’re not something I need.” She also emphasized how adapting or copying the lyrics, which were composed specifically for the music, into sign language directly would change the sign language or the original meaning of sign language.

Jung said he came to “know that people became interested in sign language” after IS made an appearance in “Permission to Dance.” For hamonthly, she’s “happy for the interest in International Sign,” but at the same time she stressed the importance for it to be an opportunity to “extend” that interest “to deaf people’s lives.” In other words, the wider public also needs to think about how deaf and other disabled people can enjoy things like concerts, meetings with fans, live streams and more without barriers to accessibility. She pointed to the process deaf people go through to attend a show as an illustrative example of such barriers: After buying a ticket, “you have to make a call to the relevant department to see if it’s possible to receive sign language interpretation, text message interpretation or shorthand, but if a deaf person needs to make a call,” they have to “use a telecommunication relay service.” Even once connected, they sometimes receive rude responses, such as immediately having their request for an interpreter turned down. When that happens, they may even fight for their rights by sending documents through an organization. hamonthly said there are many deaf people “who feel worn down but won’t give up on trying to see someone they like.”

By the same token, there’s still a lot to be done about problems of cultural accessibility in Korea. To be sure, more and more effort is being made to apply the barrier-free concept physically and in policy in consideration of accessibility for the disabled and the elderly. Korean-language closed captioning is an example of a barrier-free service that’s well known to people without disabilities and began to be offered on various over-the-top (OTT) media services starting with the introduction of Netflix in the country. In closed captions, details about the speakers and other auditory details are provided in the subtitles along with the characters’ dialog. There are also audio description services that deliver visual information through spoken word for the blind and those with limited vision. As influential global companies begin to provide closed captioning and audio description around the world, voices have recently risen up asking for these services on similar domestic platforms as well, and change is happening. hamonthly, however, said that Korean subtitles still aren’t readily provided for all content, and that she’s “baffled when there’s English subtitles on some Korean media but no Korean subtitles.” It’s also difficult to find subtitles for shows that are currently on air; there’s usually a waiting period involved before they’re added. Jung said this creates a problem where people have to watch “whatever’s provided, not what they want,” meaning “the people that subtitles are relevant for don’t have the freedom of choice.” Jung emphasized the point, noting how “interpretation through sign language has become more visible than ever because of emergency broadcasts during the pandemic, but there’s still problems when it comes to increasing the quality of sign language interpretation as well as its coverage, which only amounts to about 7% of everything broadcast.” OTT and similar services aren’t a complete solution due to the “burden of the cost” and the “problem of accessibility for elderly people who have difficulty understanding and using subtitles.”

hamonthly said she has a “hard time feeling any real change” even though barrier-free issues have recently come to the forefront. For example, the number of domestic movies in theaters with Korean subtitles and the number of screenings that show them is very low. Alternative technological solutions, like “smart glasses or providing the movie script,” do exist, but they’re not in use, she said, explaining that it’s hard to feel any real change because the lack of options means she has “to fit myself into the existing framework.” There remain problems beyond the films themselves as well. Kim Soo-Jung, the director of the Korean Barrier Free Films Committee (KOBAFF), who create barrier-free subtitles for movies and hold the Seoul Barrier Free Film Festival, criticized every part of the [movie-going] process—from entering the building and buying tickets, to getting into the theater and enjoying the show—for being littered with difficulties. “The use of kiosks has become an issue lately as well. It’s also difficult for blind people to know which direction the arrows point in the event of an emergency evacuation,” suggesting all these things need to be improved.

The same can be said of live performances. Kim Minjung is the producer of the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture, which participated in the barrier-free performance project held as the Namsan Arts Center 2019 seasonal program. Kim explained that it was necessary to “supplement or upgrade the venue facilities in order to improve physical accessibility” at that time, including overhauling Braille information signs and tactile paving for the blind, as well as making sure there would be no problems for wheelchair movement. In addition to exhibition halls, tourist attractions and performance venues, there are still considerations and improvements to be made around everyday places so that everyone can freely access them and the information and media found there. hamonthly explained that long shows featuring several performers should have two to three signers at minimum who can take turns and who are situated in front of deaf audience members. She also believes there needs to be consideration over “where the signers should be for standing seats” and how to carry on in “the event that several deaf people request” their services. She added that, even if interpretation for sign language is provided, if it isn’t sufficiently publicized, the service will ultimately go unused by those it benefits. Appropriate legal improvements must also be made to address such inadequacies. At the same time, Kim Soo-Jung said, “Even if you’re interpreting the same sentence, with what sensibilities you are interpreting it with is important.” As such, any improvements made to society should involve a willingness to communicate with the parties they impact.

“Since two or three years ago, different barrier-free shows have been produced,” Kim Minjung said. In other words, the problems that always existed with going to theaters are only now coming to light. Kim said “there were different issues at every performance” and that she talked with the directors about, for example, “where to station signers” in a performance with several actors “and how the auditory and visual information will be conveyed through text message interpretation and audio description.” Kim Soo-Jung also described how, with the recent increased need for closed captions on OTT services, a problem where different platforms repeat the effort of writing their own subtitles for the same shows “has now become apparent.” The fact that signers are now being employed for performances is not a one-stop solution to the whole problem; inevitably, there’s still more challenges to follow.

The “barrier” in barrier-free, said Jung, is another way to say “communication between the Deaf community and the rest of the world.” This ties into what Kim Minjung said at a forum—that accessibility isn’t “a value brought forward by one group’s calls for change, but a mindset” held by “all of society.” She explained the principle of accessibility: The creation and enjoyment of art is being discussed in the arts field “in terms of not categorizing the disabled or treating them as unusual beings but, from children to the elderly, as individual subjects with distinct personalities.” Barrier-free ideals, which stem from problems of spatial accessibility, ultimately are designed to benefit more than just the disabled. The elevators installed at subway stations in response to the struggle to guarantee disabled people’s right to free movement also prove to be convenient with elderly people who aren’t disabled. KOBAFF’s dementia-friendly screenings, Kim Soo-Jung explained, not only provide a barrier-free movie experience with plenty of explanations, but also focus on providing a visually and psychologically comfortable environment in which dementia patients who feel uncomfortable in unfamiliar places. The process of creating a barrier-free world also results in experiences that are a little more helpful for people without disabilities in their day-to-day lives. “I saw a comment from someone who can hear saying that it’s easier to understand what they’re watching on their OTT service when they switch on the Korean closed captioning,” hamonthly said. “What’s good for people who can hear also provides conveniences to deaf people and those who are hard of hearing.”

Despite all this, Netflix only started to add subtitles to their service because the National Association of the Deaf in the US won a lawsuit against them in 2010. Clearly, securing rights for disabled people that are not already provided to them by law should always be prioritized in this discussion. Barrier-free policies like all those mentioned in this article are now being implemented little by little everywhere in society and are the result of a variety of movements carried out by disabled people over a long period of time. On the other hand, though, the discussion cannot be otherized into a conversation far removed from people without disabilities. It’s a problem we all must solve together—you, me, the people close to me, and all members of society.

The first person we see in the “Permission to Dance” music video is a woman working at a restaurant. The video shows a number of other people—mail carriers, cleaners, children, students—who live and work all around us, but who belong to a class of people whose struggles since the pandemic hit aren’t visible enough. It’s surely no coincidence that BTS chose to shine the spotlight on such individuals in their music video while also using IS. BTS also had signers at some of their performances two years ago. What’s more important than what BTS did, however, is the ongoing discussion around the issues being raised and whether they can result in something that improves the lives of the deaf people and, moreover, all the disabled people. This, hamonthly said, needs “continuous attention, not curiosity.” And she added one more thing.

“There are more deaf people around you than you think.”

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.

- How BTS sings of healing the mind2021.02.01

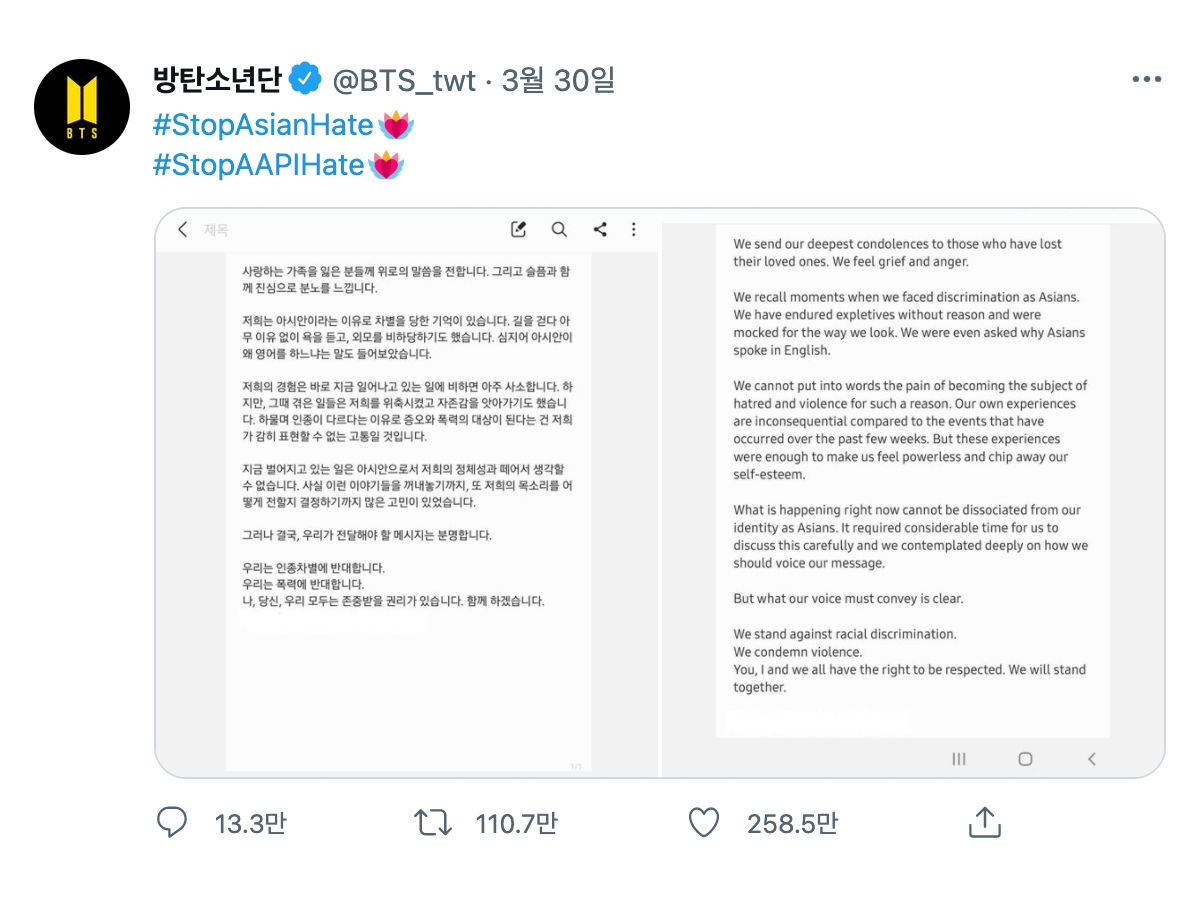

- Stories After #StopAsianHate2021.06.28

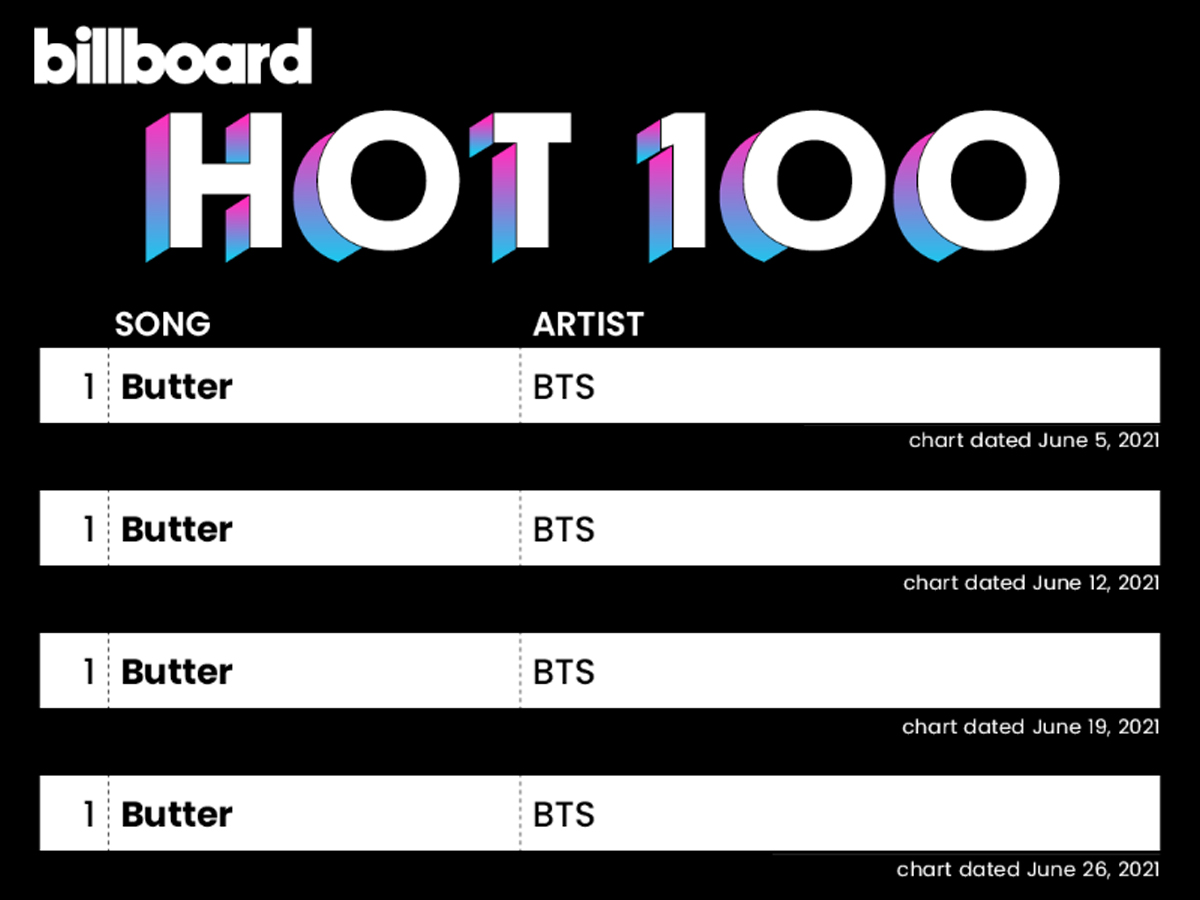

- What BTS achieved in the US2021.07.12

- The Power of BTS’ Music2021.07.21

- How Permission to Dance came to be2021.08.12