FEATURE

BTS and the Grammys: Why now?

The significance behind BTS’s Grammy odds

2020.11.16

One of the questions surrounding next February’s 63rd Grammy Awards is whether or not BTS will receive any award nominations. Forbes took note last November when BTS wasn’t nominated for the most recent Grammys, sizing up the response to the fruits of their labor that year: “Grammy nominees and winners throughout history reveal a voting bias within the Academy,” they wrote, “as artists of color are repeatedly “othered.” Likewise, Rolling Stone criticized “the failure to acknowledge K-pop at awards shows which stands in stark contrast to the music industry’s day-to-day reality.” BTS’ short performance with Lil Nas X at the 62nd Awards was met with positive reviews, though the group received no nomination. They also presented the award for Best R&B Album at the 61st Grammys in 2019, after which the suits they wore were put on display at the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles later that year in November. Yet the only nomination to bear their name at the show was given to the album art director for Best Recording Package. Whether this was a deliberate choice by the Grammys, as suggested by Forbes and Rolling Stone, can’t be said for sure. What is clear, however, is that a wide discrepancy exists between the spotlight they shine on BTS and the nominations they hand out.

-

©️ Grammy Awards

©️ Grammy Awards

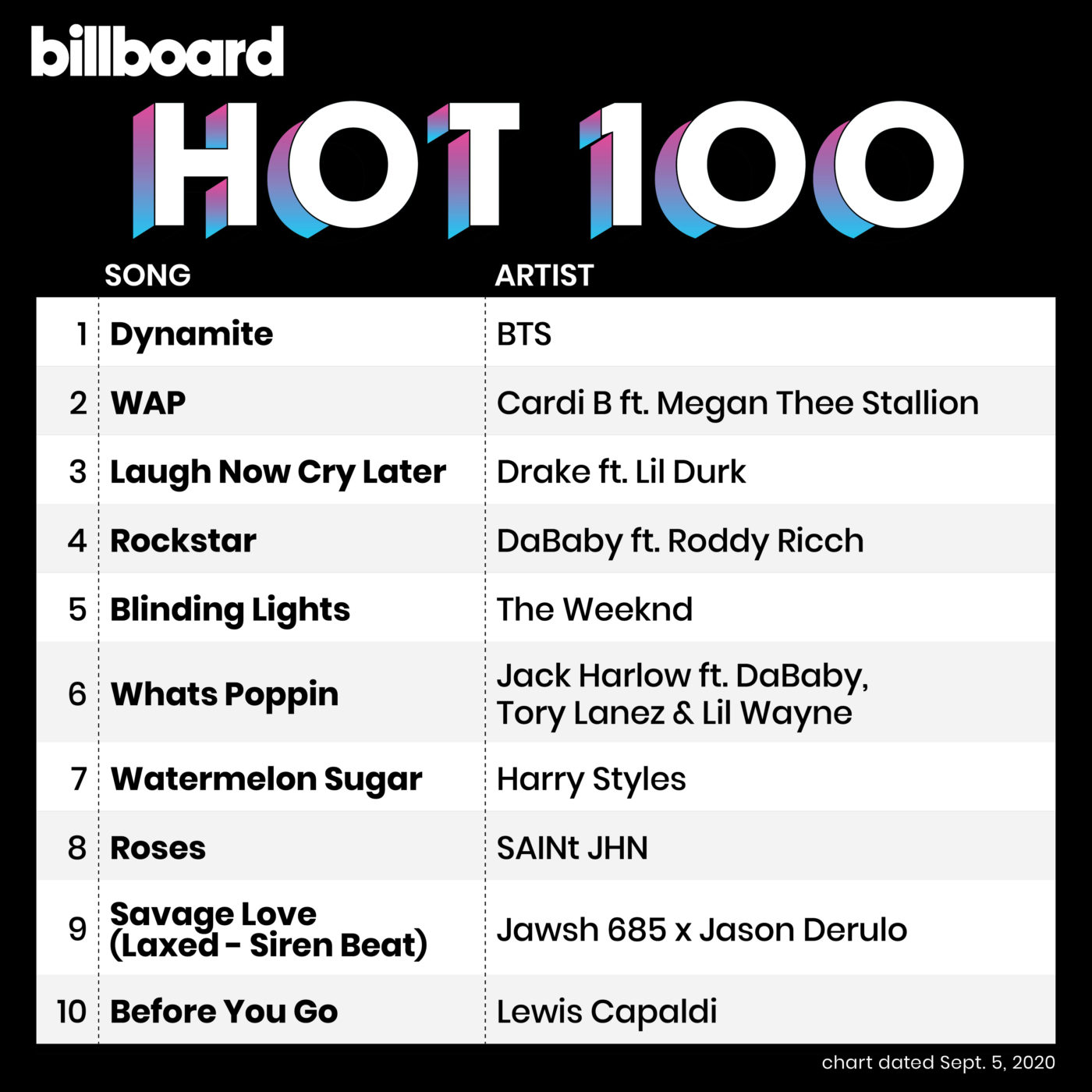

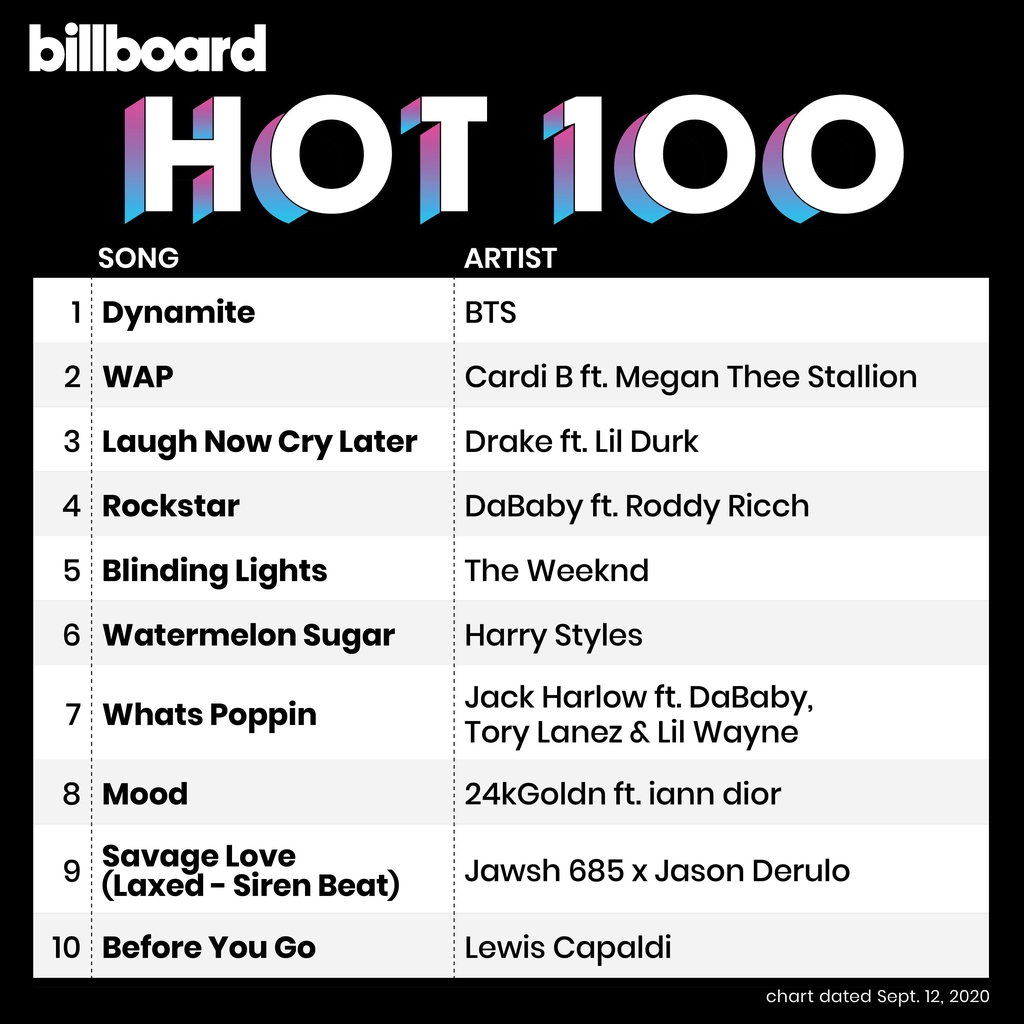

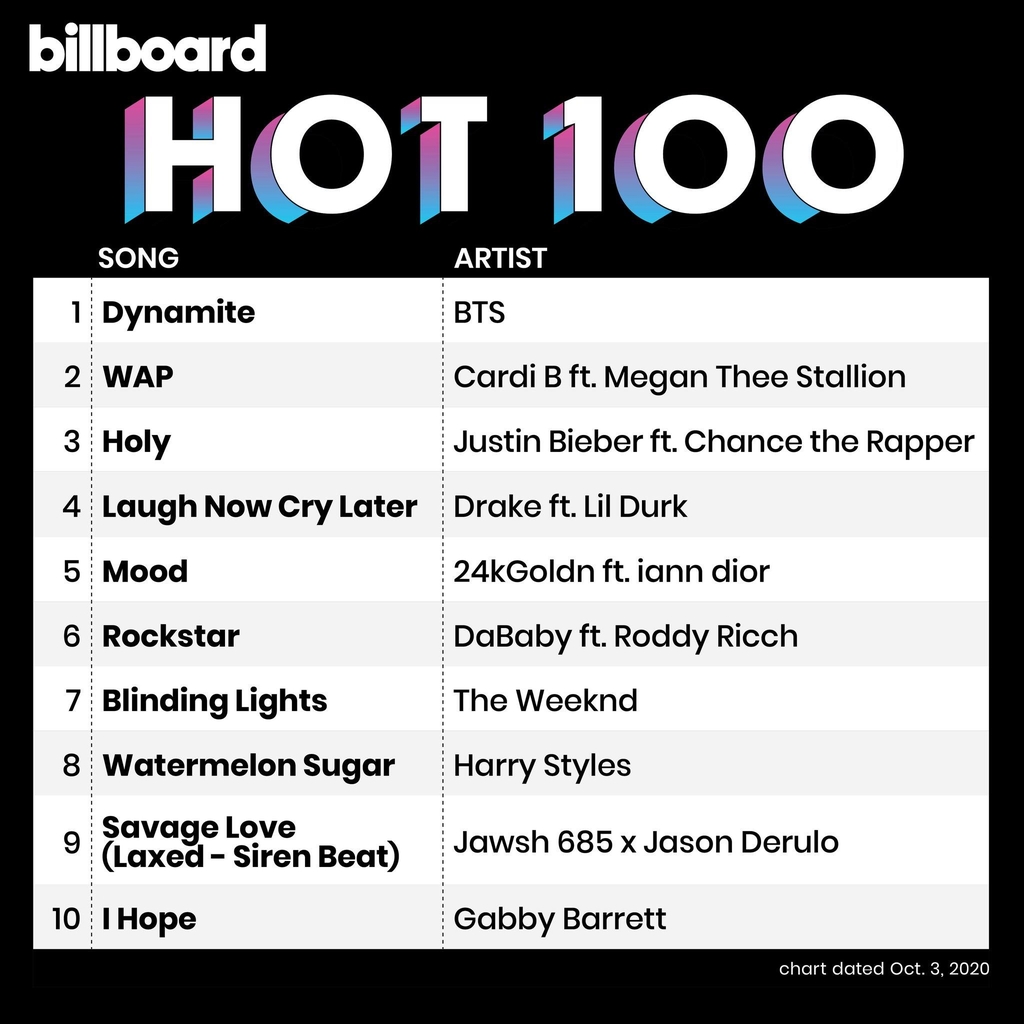

BTS’s “Dynamite” topped the Billboard Hot 100 chart for the first two weeks of September consecutively. It’s the third time that an Asian artist has reached the top spot, after “Sukiyaki” in 1963 and “Like a G6” in 2010. According to Nielson Music’s 2020 Mid-Year Report, BTS’s "Map of the Soul: 7" was the only album in the United States to sell more than 500,000 physical copies during the first half of the year. BTS also ranked second among pop artists, after Billie Ellish, with a total of 1.417 million units, a metric which translates physical album purchases, digital music downloads and streaming figures into album sales. Furthermore, they outpaced the Beatles, the only other ensemble to surpass one million total units. And it’s not just the group’s commercial performance: BTS fans, under the collective moniker ARMY, have raised the bar for fandom participation, inundating the Dallas Police Department’s iWatchDallas app with fan-recorded “fancam” videos to prevent officers from tracking the moves of Black Lives Matter protesters, and donating over $1 million to the BLM movement. Not only have BTS achieved phenomenal commercial success in the Western-oriented American music industry, they have become a defining symbol of the times, leading a vast ARMY of diverse identities around the world. Were they to win or be nominated for a Grammy, BTS would be writing one more line in the pages of their unexpected and unpredictable history. However, their story wouldn’t be forgotten even if they were never to win the award. If there’s particular meaning behind the decision whether or not to award BTS at the Grammys now, it can be gleaned by looking closer at current social issues.

Even before BLM became a hot-button issue in 2020, the Grammys had long been a heated arena for identity politics. After Macklemore and Ryan Lewis beat out Kendrick Lamar to win Best New Artist and three more awards in the Rap category at the 56th Grammy Awards in 2014, Macklemore posted an apology on his Instagram to Lamar, saying, “I wanted you to win.” Three years later, at the 2017 Grammys, while Adele took home nearly every single one of the highest honors—winning Album of the Year, Record of the Year, and Song of the Year, and missing only Best New Artist—plus two additional trophies, Beyoncé, whose album "Lemonade" had been released to critical acclaim, won only the Best Progressive R&B Album (then Best Urban Contemporary Album) and Best Music Video awards. Even Lamar, whose 2015 and 2017 albums "To Pimp a Butterfly" and "DAMN." received Metacritic scores of 96 and 95 respectively, left the Grammys without any of the top prizes. Whether the panel of voting members, long criticized under the hashtag “#GrammysSoWhite,” have intentionally ignored Black artists remains up for debate. For its part, Billboard identified a history of the awards show consistently shunning hip hop and its related genres from the main awards, with legendary artists such as Tupac, Notorious B.I.G., Nas, Snoop Dogg, Ice Cube, A Tribe Called Quest, MC Lyte, N.W.A, Run-DMC, Public Enemy and more having never tasted the glory that comes with winning a Grammy. Billboard also took issue with the way hip hop artists are boxed into genre awards and left out from the major ones. In 2017, Drake explained how his song “Hotline Bling,” which had won Best Rap Performance, is not, in his opinion, a rap song, complaining that the Grammys only saw him as a rapper because he’s Black, and had restricted his music to the rap genre and so not considered him for any of the principal categories. When the MTV Video Music Awards (VMAs) added a K-pop category last August, this struck some BTS fans as perhaps a similarly discriminatory move to lock K-pop artists out of the main awards. As seen with BTS, K-pop now faces the same problem that hip hop has suffered from for so long.

That’s not to say the Grammys haven’t changed at all. Childish Gambino, who in “This is America” reveals the racism and hatred present in American society, received a total of four awards for his song at the 61st Grammys, including the major Song of the Year and Record of the Year awards. There also appeared to be more progress made this year. Billie Ellish’s five wins, which included all four major awards, as well as Lizzo and Lil Nas X’s many nominations and wins point to a Grammys ceremony that increasingly pays attention to teenage women, Black artists, and social media influencers. This latest move, however, is the result of a slow and protracted fight. In September, Billboard pointed out that the Grammys have been criticized in recent years for being white- and male-dominated, predicting that it would be difficult for next year’s Grammy Awards to ignore ongoing racial issues. In other words, the Grammys’ recent swing toward awarding Black artists has only come about after facing sharp criticisms like #GrammysSoWhite and in the wake of serious issues like BLM. Only a few years ago, in 2017, Frank Ocean complained about the awards ceremony, detailing why he didn’t submit his documents to register for the 59th Grammys. In a similar fashion, Jay-Z and Beyoncé have been absent from the ceremony the past two years. Black artists, long vocal about change, have succeeded in improving the Grammys, but its problematic approach to race still remains. And the narrative of Asian and K-pop artists standing up to the Western music industry and, by extension, the Grammy Awards, begins now with BTS. In other words, whether BTS wins this time will act as a litmus test for the current state of the Grammys.

It’s difficult to say with confidence that the Grammys have intentionally snubbed K-pop and other Asian artists. The Western-centric US music market isn’t exactly full of examples of Asian musicians who have made any meaningful commercial impact: Chinese American artist ZHU, Korean American singers Yaeji and Ted Park, US-based artists like Taiwanese producer Gill Chang and Malaysian singer Yuna, London-based house DJ Park Hye Jin and many others are all highly praised artists who have yet to show significant commercial performance. Even if the definition of K-pop were expanded from the relatively narrow sense of idols to encompass all music made by Korean artists or in the Korean language, the success of Psy’s “Gangnam Style” in 2012 didn’t immediately solidify the global success of Korean music. And it’s with this point that BTS’s “Dynamite” can be seen as controversial. Here, the artist is Korean, but the genre is disco and the lyrics are in English. It’s the forty-third time in history that a song has debuted at the top spot on the Billboard Hot 100, spending two consecutive weeks in the position before returning there again on its fifth week. When it was revealed that the return stemmed from the popularity of various “Dynamite” remixes, Forbes pointed out how this is commonly the strategy of choice in the music industry, reminding readers that BTS used the same approach as Lady Gaga and Ariana Grande’s “Rain on Me,” Doja Cat’s “Say So,” and Megan Thee Stallion’s “Savage,” adding that, “Every pop star is competing for the same prize--a No. 1 hit--and the savviest artists with the biggest fan bses take home the gold.” In other words, BTS simply has too many fans to justify the biased view that K-pop idoldom is a genre whose popularity is limited only to an isolated fanbase; has released music that, considering its English lyrics and disco bent, is best classified as pop; and has broken records that would be surprising in the current US market regardless of the artist behind them. How will BTS’s feat of overcoming the hurdles of race, genre, and nationality regulated by the Western music industry be received at the Grammys?

Even before BLM became a hot-button issue in 2020, the Grammys had long been a heated arena for identity politics. After Macklemore and Ryan Lewis beat out Kendrick Lamar to win Best New Artist and three more awards in the Rap category at the 56th Grammy Awards in 2014, Macklemore posted an apology on his Instagram to Lamar, saying, “I wanted you to win.” Three years later, at the 2017 Grammys, while Adele took home nearly every single one of the highest honors—winning Album of the Year, Record of the Year, and Song of the Year, and missing only Best New Artist—plus two additional trophies, Beyoncé, whose album "Lemonade" had been released to critical acclaim, won only the Best Progressive R&B Album (then Best Urban Contemporary Album) and Best Music Video awards. Even Lamar, whose 2015 and 2017 albums "To Pimp a Butterfly" and "DAMN." received Metacritic scores of 96 and 95 respectively, left the Grammys without any of the top prizes. Whether the panel of voting members, long criticized under the hashtag “#GrammysSoWhite,” have intentionally ignored Black artists remains up for debate. For its part, Billboard identified a history of the awards show consistently shunning hip hop and its related genres from the main awards, with legendary artists such as Tupac, Notorious B.I.G., Nas, Snoop Dogg, Ice Cube, A Tribe Called Quest, MC Lyte, N.W.A, Run-DMC, Public Enemy and more having never tasted the glory that comes with winning a Grammy. Billboard also took issue with the way hip hop artists are boxed into genre awards and left out from the major ones. In 2017, Drake explained how his song “Hotline Bling,” which had won Best Rap Performance, is not, in his opinion, a rap song, complaining that the Grammys only saw him as a rapper because he’s Black, and had restricted his music to the rap genre and so not considered him for any of the principal categories. When the MTV Video Music Awards (VMAs) added a K-pop category last August, this struck some BTS fans as perhaps a similarly discriminatory move to lock K-pop artists out of the main awards. As seen with BTS, K-pop now faces the same problem that hip hop has suffered from for so long.

That’s not to say the Grammys haven’t changed at all. Childish Gambino, who in “This is America” reveals the racism and hatred present in American society, received a total of four awards for his song at the 61st Grammys, including the major Song of the Year and Record of the Year awards. There also appeared to be more progress made this year. Billie Ellish’s five wins, which included all four major awards, as well as Lizzo and Lil Nas X’s many nominations and wins point to a Grammys ceremony that increasingly pays attention to teenage women, Black artists, and social media influencers. This latest move, however, is the result of a slow and protracted fight. In September, Billboard pointed out that the Grammys have been criticized in recent years for being white- and male-dominated, predicting that it would be difficult for next year’s Grammy Awards to ignore ongoing racial issues. In other words, the Grammys’ recent swing toward awarding Black artists has only come about after facing sharp criticisms like #GrammysSoWhite and in the wake of serious issues like BLM. Only a few years ago, in 2017, Frank Ocean complained about the awards ceremony, detailing why he didn’t submit his documents to register for the 59th Grammys. In a similar fashion, Jay-Z and Beyoncé have been absent from the ceremony the past two years. Black artists, long vocal about change, have succeeded in improving the Grammys, but its problematic approach to race still remains. And the narrative of Asian and K-pop artists standing up to the Western music industry and, by extension, the Grammy Awards, begins now with BTS. In other words, whether BTS wins this time will act as a litmus test for the current state of the Grammys.

It’s difficult to say with confidence that the Grammys have intentionally snubbed K-pop and other Asian artists. The Western-centric US music market isn’t exactly full of examples of Asian musicians who have made any meaningful commercial impact: Chinese American artist ZHU, Korean American singers Yaeji and Ted Park, US-based artists like Taiwanese producer Gill Chang and Malaysian singer Yuna, London-based house DJ Park Hye Jin and many others are all highly praised artists who have yet to show significant commercial performance. Even if the definition of K-pop were expanded from the relatively narrow sense of idols to encompass all music made by Korean artists or in the Korean language, the success of Psy’s “Gangnam Style” in 2012 didn’t immediately solidify the global success of Korean music. And it’s with this point that BTS’s “Dynamite” can be seen as controversial. Here, the artist is Korean, but the genre is disco and the lyrics are in English. It’s the forty-third time in history that a song has debuted at the top spot on the Billboard Hot 100, spending two consecutive weeks in the position before returning there again on its fifth week. When it was revealed that the return stemmed from the popularity of various “Dynamite” remixes, Forbes pointed out how this is commonly the strategy of choice in the music industry, reminding readers that BTS used the same approach as Lady Gaga and Ariana Grande’s “Rain on Me,” Doja Cat’s “Say So,” and Megan Thee Stallion’s “Savage,” adding that, “Every pop star is competing for the same prize--a No. 1 hit--and the savviest artists with the biggest fan bses take home the gold.” In other words, BTS simply has too many fans to justify the biased view that K-pop idoldom is a genre whose popularity is limited only to an isolated fanbase; has released music that, considering its English lyrics and disco bent, is best classified as pop; and has broken records that would be surprising in the current US market regardless of the artist behind them. How will BTS’s feat of overcoming the hurdles of race, genre, and nationality regulated by the Western music industry be received at the Grammys?

-

©️ Billboard

©️ Billboard

-

©️ Billboard

©️ Billboard

-

©️ Billboard

©️ Billboard

The American Music Awards (AMAs) have been deciding their awards by popular vote since 2006, and the Billboard Music Awards (BBMAs) measure commercial success based on data from their own charts. By contrast, the Grammys first collect their votes from a group of singer-songwriters, producers, composers and others in the music industry who select 20 candidates, which are further narrowed down, by a nomination committee of at least 20 board-approved members, to eight nominees eligible for the four major Grammy awards. The Final Report of the Recording Academy Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion, published last December, outlines explanations from former executives who state that the nomination review committees are intended to review member votes in order to ensure a fair process for determining candidates and to include lesser-known artists and their works. In other words, the Grammys, as a comparatively conservative awards ceremony, instead follows a voting and nomination system that should allow it to focus purely on musical merit. As the Task Force’s report points out, however, although the increase from five to eight candidates for the top prizes has improved conditions such that a more diverse group of artists can be nominated, in areas where competition is fierce, nominees with a mere 13 percent of the votes for any particular award can win. Also, according to Billboard’s report, the nominating review committee decides the finalists without any knowledge of the rankings given to the 20 potential nominees by community members when it takes over after the first round of voting. Moreover, the members of the committee are appointed after consultation with the Chair of the Recording Academy’s Board of Trustees, with the composition of the Board coming out to 65% male and 63% white as of December 2019. Lack of representation for the opinions of the entire voting population, subjective criteria by the nomination review committee, and diversity within the organization are all matters the Grammys need to address moving forward.

That’s not to say that the Grammys haven’t been trying to secure internal diversity. According to the same Billboard article, the Recording Academy had recruited 200 new voting members in 2018 and 590 in 2019, with a focus on enlisting more women, ethnic minorities and young voters over the past two years. These efforts will gradually help the Grammys choose music that is more diverse and representative of current trends. And BTS can be a measure of how far the line on the graph of change has advanced: How much attention are the Grammys prepared to give to keywords like K-pop, Asia and boy bands? BTS received “universal acclaim,” the highest ranking at Metacritic, for their album Map of the Soul: 7 released in February, and have been praised by Rolling Stone as “a whole new kind of global pop phenomenon,” as well as “a success story that defies conventional wisdom about the kinds of music Americans will tune into” by The Wall Street Journal. And “Dynamite” pairs a disco flavor alongside a message of hope for a post-COVID future. Simply put, BTS’s music is polished, diverse and topical. But even if BTS aren’t awarded or at least nominated at the upcoming Grammy Awards, that won’t mean the judges have made the wrong choice, of course. Still, it’s fair to ask just how far the Grammys are willing to reach, both at home in the US and abroad, to embrace musical diversity and current trends. Considering that the Korean film "Parasite" won four major awards at this year’s Academy Awards, including not only Best International Feature Film—reserved for foreign language films made outside the US—but also Best Picture, the question becomes that much more pertinent.

The word “K-pop” appears exactly once in the Task Force report. Here, where it finds Asian American artists are being pigeonholed into K-pop and African American executives are only represented in rap and hip hop, the report suggests that “the music industry needs to have a more expansive view on what constitutes diversity within the industry.” The main takeaway from this solitary mention is not that the report lacks sufficient references to K-pop or Asians for an investigation that claims to be about diversity. Rather, we need to see how the prejudice attached to the word “K-pop” is such that, as is the case with BTS, not only does it limit artists who begin their careers as K-pop musicians, but it also confines some US-based artists simply because they’re Asian. What matters most in the end is not whether BTS’s latest offerings are pop, K-pop, or any other label. Nor is this a debate over whether or not they’re idols or a boy band. Taken altogether, this is a question of how much someone’s identity influences the way others receive their art. Through its trials in the US, BTS has spun this kind of bias into critical acclaim, Billboard-topping commercial success, and historical, transformative wins at the AMAs and BBMAs. It warrants asking again: What kind of music will the Grammys remember “Map of the Soul: 7” and “Dynamite” as when labels like K-pop and Asia are erased?

That’s not to say that the Grammys haven’t been trying to secure internal diversity. According to the same Billboard article, the Recording Academy had recruited 200 new voting members in 2018 and 590 in 2019, with a focus on enlisting more women, ethnic minorities and young voters over the past two years. These efforts will gradually help the Grammys choose music that is more diverse and representative of current trends. And BTS can be a measure of how far the line on the graph of change has advanced: How much attention are the Grammys prepared to give to keywords like K-pop, Asia and boy bands? BTS received “universal acclaim,” the highest ranking at Metacritic, for their album Map of the Soul: 7 released in February, and have been praised by Rolling Stone as “a whole new kind of global pop phenomenon,” as well as “a success story that defies conventional wisdom about the kinds of music Americans will tune into” by The Wall Street Journal. And “Dynamite” pairs a disco flavor alongside a message of hope for a post-COVID future. Simply put, BTS’s music is polished, diverse and topical. But even if BTS aren’t awarded or at least nominated at the upcoming Grammy Awards, that won’t mean the judges have made the wrong choice, of course. Still, it’s fair to ask just how far the Grammys are willing to reach, both at home in the US and abroad, to embrace musical diversity and current trends. Considering that the Korean film "Parasite" won four major awards at this year’s Academy Awards, including not only Best International Feature Film—reserved for foreign language films made outside the US—but also Best Picture, the question becomes that much more pertinent.

The word “K-pop” appears exactly once in the Task Force report. Here, where it finds Asian American artists are being pigeonholed into K-pop and African American executives are only represented in rap and hip hop, the report suggests that “the music industry needs to have a more expansive view on what constitutes diversity within the industry.” The main takeaway from this solitary mention is not that the report lacks sufficient references to K-pop or Asians for an investigation that claims to be about diversity. Rather, we need to see how the prejudice attached to the word “K-pop” is such that, as is the case with BTS, not only does it limit artists who begin their careers as K-pop musicians, but it also confines some US-based artists simply because they’re Asian. What matters most in the end is not whether BTS’s latest offerings are pop, K-pop, or any other label. Nor is this a debate over whether or not they’re idols or a boy band. Taken altogether, this is a question of how much someone’s identity influences the way others receive their art. Through its trials in the US, BTS has spun this kind of bias into critical acclaim, Billboard-topping commercial success, and historical, transformative wins at the AMAs and BBMAs. It warrants asking again: What kind of music will the Grammys remember “Map of the Soul: 7” and “Dynamite” as when labels like K-pop and Asia are erased?

Article. Rieun Kim, Yejin Lee

Design. Lee3am

Copyright © Weverse Magazine. All rights reserved.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution prohibited.